Marie Catherine Mesnard

Géricault Life

Map of New Orleans and vicinity, (detail) Pintado, Vicente Sebastián, 1774-1829. Trudeau, Charles Laveau, approximately 1750-1816. Created / Published [1819] “1873 copy of 1804 map copied by Pintado (in Havana in 1819) verified by Pilié in 1838. Map information by Pintado 1795-96 – set down by Trudeau in 1804.” Image and explication (abridged) Library of Congress.

Stories Behind Stories

The presence of women such as Marie Catherine Mesnard and Adélaide Sarba in historical narratives, and the lack thereof, is particularly important for those studying Théodore Géricault, an individual defined by his sometimes complex relationships with female friends, family members, and lovers – especially when one family member is also a lover – as was the case with Alexandrine Modeste de Saint Martin (Caruel), the mother of Géricault’s only known child we now know, and wife to Théodore’s uncle, Jean Baptiste Caruel.

Marie Catherine’s Mesnard was born in Angoulême, in south-western France, sometime around 1740. Her father Michel Mesnard, écuyer, died sometime before April, 1767. He and his wife dame Françoise Saulnier de Pierrelevée had at least two children: Jean Mesnard, enseigne de vaisseux du roi, a junior officer in the French navy, and Marie Catherine Mesnard. Marie Catherine Mesnard married her first husband Jean Chaigne, demeurement habituellement à Saint Domingue – according to archival records, on or around December 24, 1767.

We assume Marie Catherine lived in Saint Domingue with her husband Jean Chaigne after their marriage. On February 17, 1773, Marie Catherine’s brother, naval officer Jean Mesnard married Marie Jeanne Françoise Château in Cap Tiburon, in south-western Saint Domingue. Marie Anne Château was part of substantial family of plantation owners in Saint Domingue. Several male family members served in the island militia and/or in the French navy, as did Théodore Géricault’s Robillard and de Barras male relations. Jean Mesnard belonged to the same generation of naval officers as André de Barras la Villette, the elder brother of Étienne de Barras. (We discuss both de Barras brothers and their relations with Théodore Géricault elsewhere.) In 1773, Jean Mesnard, écuyer, was based in Port-au-Prince and commanded a brigantine. We do not know when Jean Chaigne passed away, but we do know that the Vicomte Étienne de Barras held a position of rank within this community.

The marriage of Marie Catherine Mesnard and Étienne de Barras in Jeremie, Saint Domingue is recorded in two documents, at least. The first from the état civil, or the registry of births, marriages, and deaths of Jeremie, Saint Domingue, describes the celebration of their marriage on June 8, 1790. The second document, a copy of their marriage contract – the original signed on June 7, 1790, surfaced at a sale at the Hôtel de Drouot in 2002. The copy was created in New York, early in 1804, and provides details about the marriage contract Marie Catherine Mesnard signed with Chevalier Étienne de Barras on June 7, 1790, and about the couple’s time together in America. (Généalogie et Histoire de la Caraïbe, Bulletin 155 : January 2003; p. 3709 “Old Documents.”)

The summer of 1790 was difficult for almost everyone in Saint Domingue. Marie Catherine Mesnard and Étienne de Barras in 1790 were probably among the many opposed to extending equal rights as citizens of the republic to free people of color. The battle broke out soon after. As we have discussed elsewhere, Étienne de Barras employed his military prowess during this period against former slaves and people of color fighting for equality, and later as an officer fighting alongside the British against Republican French forces. Marie Catherine Mesnard and Étienne de Barras eventually quit Saint Domingue for New York, arriving there individually or together no later than 1798. Étienne’s sister Marie Anne Charles de Barras and her family made a similar escape to New York two years earlier. The difference being that Marie Anne Charles de Barras and her family returned to France in 1797.

Naturalized Americans – 1803

Théodore Géricault’s relations reacted to the revolution and violence in Saint Domingue in different ways. Adélaide Sarba and her children may have crossed the Atlantic with Claude de Barras and others. Such a voyage seems unlikely, however. We know more about Marie Catherine Mesnard and her second husband Étienne de Barras.

After leaving Saint Domingue, Marie Catherine Mesnard and Étienne de Barras’s elected to remain in New York. On November 1, 1803, both were naturalized as U.S. citizens. (The Papers of Thomas Jefferson: Volume 45, 11 November 1804 to 8 March 1805, James P. McClure, Editor. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2021. p. 672, n°1) At least one other member of the extended Géricault family in Saint Domingue settled in the United States: Marie Marguerite Roullit, the sister of Katherine Roullit, a migration which we shall discuss elsewhere.

Marie Catherine Mesnard lived the final years of her life in the United States, primarily in New York. but evidently left New York with Étienne de Barras early in 1804 to build a new life in Louisiana. Her life journey from Angoulême to the ‘New World’ ended in Nueva Orleans on July 9, 1804.

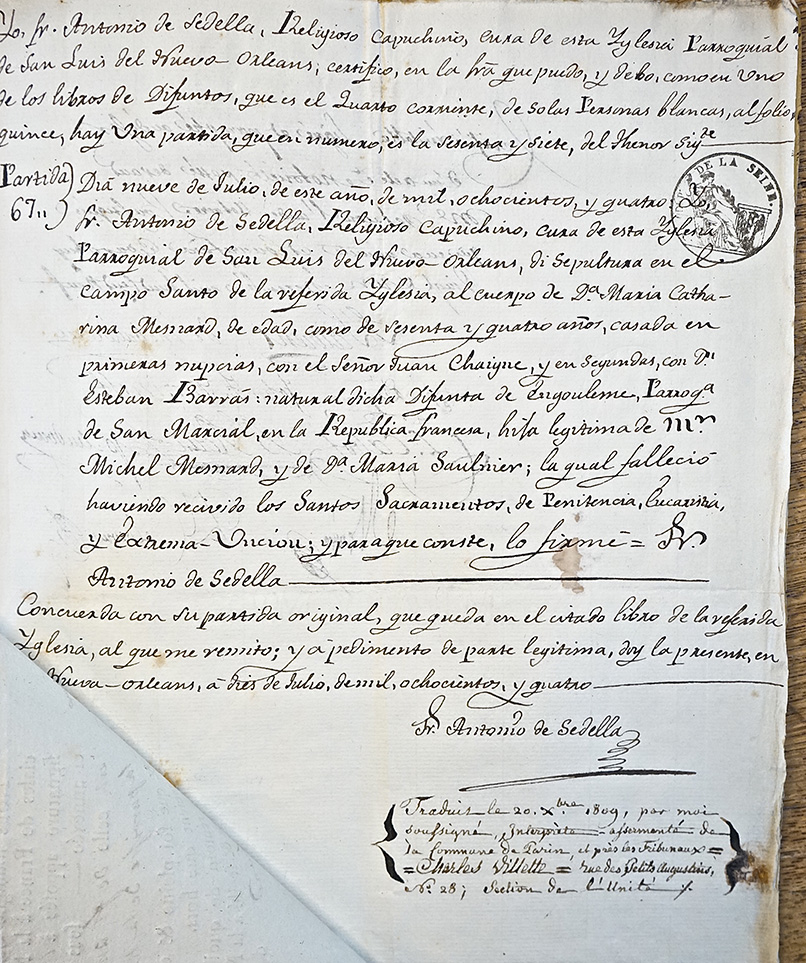

The Spanish curé of the Eglisse de Saint Louis, Antonio de Sedella, administered the last rites for Marie Catherine and saw her buried in the Nuevo Campo Santo, as Saint Louis Cemetery N° 1 was then called, in that part of the holy ground designated ‘whites only.’ The curé then recorded the ceremony in Spanish in the parish register on July 9, 1804. On July 10, 1809, curé de Sedalla provided a copy of this record to the French trade representative in New Orleans.

We know now that Étienne de Barras and Marie Catherine Mesnard remained in America and formally adopted this new nation as their own on November 1 of 1803. The 1804 copy of the couple’s marriage contract, created in early February in New York suggests the couple were in New York at that point. Six months later Marie Catherine’s life ended in New Orleans at the age of sixty-four. We do not know when Étienne de Barras departed from the United States, only that he remained there until 1805 at least.

Commentary and Context

Théodore Géricault’s Caruel and Robillard relations in Rouen and Paris almost certainly knew of Marie Catherine’s marriage to the Vicomte Étienne de Barras in 1790. We have discussed the significance of Géricault’s de Barras relations to the artist and his family frequently in this space.

News travelled slowly across the Atlantic during these years of almost uninterrupted political turmoil and war. The news of Marie Catherine Mesnard’s passing in New Orleans on June 9, 1804, may not have reached Théodore Géricault and his family in Paris until 1809.

Louis Batissier in his biography of Géricault of 1841 recounted the following anecdote: “…Géricault sometimes visited Baron Gerard. One day Gericault expressed to him the real desire he harbored to travel far, and to seek a life of adventure in foreign lands…”

An Atlantic Sensibility

The culture of New Orleans in 1804 was truly exotic: a melange of African, indigenous American peoples, and traditional European elements. The indigenous peoples, slaves, free people of color, and Europeans and Americans of various sorts in New Orleans watched as Louisiana passed from French control to Spanish, and then back to French at the beginning of the 19th century.

These dynamics of the alien versus the indigenous, the traditional versus the revolutionary, appear in different forms in much of Géricault’s art, as well as his personal life. Dynamic conflict operates like a coiled spring within so much of Géricault’s art. Contemporary witnesses report that Géricault’s imagination was fuelled by literature, as much as art: by Tasso, Milton, Byron, and Sir Walter Scott. But surely Géricault must have also been influenced by real-life accounts of people he met, knew well, and knew of through others.

Marie Catherine Mesnard’s life story made its way back across the Atlantic sometime before 1809. The story of her life and death was recorded and witnessed by individuals closely tied with the Musée français, the Robillard (Géricault) family art business. Étienne de Barras, Marie Catherine Mesnard’s second husband, survived his struggles in the Antilles and America and reconnected with family members in Paris, all of whom Géricault knew, even if Géricault did not know each well. Indeed, this sense of distance probably added to the dynamic of the alien and the exotic. Géricault was shaped by these Atlantic encounters through his direct and mediated contacts with these exotic individuals, and their stories, even as he was drawn to the attractions of Asia and the Middle East, in more than one sense – a theme we will explore in greater detail shortly.

Antonio de Sedella, Curé: copy of the parish record (église Saint Louis) of the death and burial of Marie Catherine Mesnard in New Orleans on 9 July, 1804, translated into French on December 20, 1809, a document of the Acte de Notoriéte Constatant que mad. Barras à son décès n’a pour laissée d’enfants de son mariage, 21 December, 1809, (detail), A.N MC/ET/XIX/935 Notaire Delacour, Image Courtesy Archives Nationales (France).