Adélaide Sarba

Géricault Life

1821 Le général Toussaint Louverture reçevant un général anglais (lithograph, detail) *, François Grenier de Saint Martin. Image courtesy of Musée du Quai Branly, Paris.

Background

Théodore Géricault and his family had close connections to the de Barras family from 1788. The best-known member of the de Barras family is likely Paul de Barras, who helped depose Robespierre and his allies in 1794, organized the slaughter of royalist insurrectionists in Paris in 1795, and went on to rule France as a kind of despot until he was deposed by Napoleon in 1799.

Claude de Barras was a leading figure of the de Barras family in Saint Domingue and in Paris after. Claude de Barras died in Paris on January 24, 1807, in apartments near those of his sister Marie Anne Charles de Barras and her family at n°9 rue de la Concorde in Paris. Brother and sister lived at the same address. Claude de Barras was close to his sister and her husband Louis Robillard de Péronville, who founded the Musée français with Pierre Laurent, another de Barras relation and a skilled engraver, in Paris in 1802. Claude de Barras also owned a small share of this family business. The Musée français produced exquisite engravings of the paintings, statues and bas-reliefs of the national collection at the Louvre from 1803 to 1809. As we have discussed, Théodore Géricault and his family wre closely allied with this family and the Musée français.

Louis Robillard de Péronville was born in Rouen in 1750 and moved to France’s island colony of Saint Domingue, where the Robillard family owned several plantations, at some later date. There Claude de Barras helped arrange the marriage of Louis Robillard de Péronville to his sister Marie Anne Charles at the de Barras family residence in Le Cap, the port city on the northern coast, in 1788. Until now that is all anyone knew of Claude de Barras. As it turns out, Claude de Barras, Adélaide Sarba and the children the couple produced, may have influenced the way Théodore Géricault viewed his world and his role as an artist.

Adélaide Sarba and her children

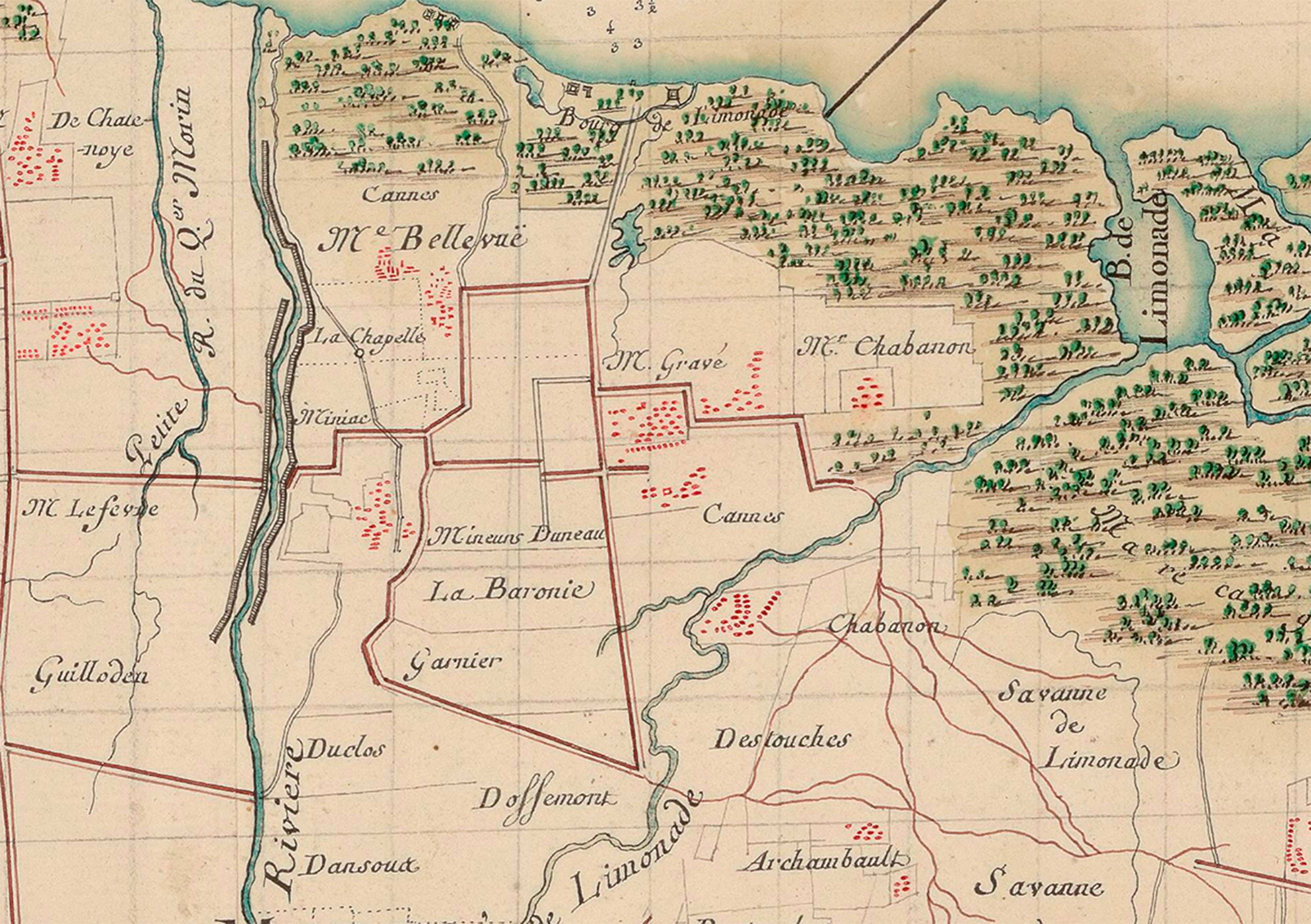

Adélaide Sarba lived in the parish of Limonade in Saint Domingue (modern Haiti) at the end of the 18th century. Together, Adélaide Sarba and Claude de Barras produced eight children over the course of a decade or more. In one acte de baptisme (see below) Adélaide Sarba is identified as a mulâtresse libre ( a free woman of African and European ancestry in equal parts). All eight children were born before 1793 in France’s richest slave colony.*

We do not know how many of Théodore Géricault’s relations in the colony survived Saint Domingue’s violent struggle for freedom and independence, a struggle which apparently so interested the artist. Nor do we possess any concrete evidence suggesting that Géricault had any of his Saint Domingue relations in mind when painting or drawing people of color in portraits and smaller pieces. We can state with certainty and for the first time, however, that Théodore Géricault had eight distant cousins who were people of color in Saint Domingue in 1793. We present this evidence to our readers here.

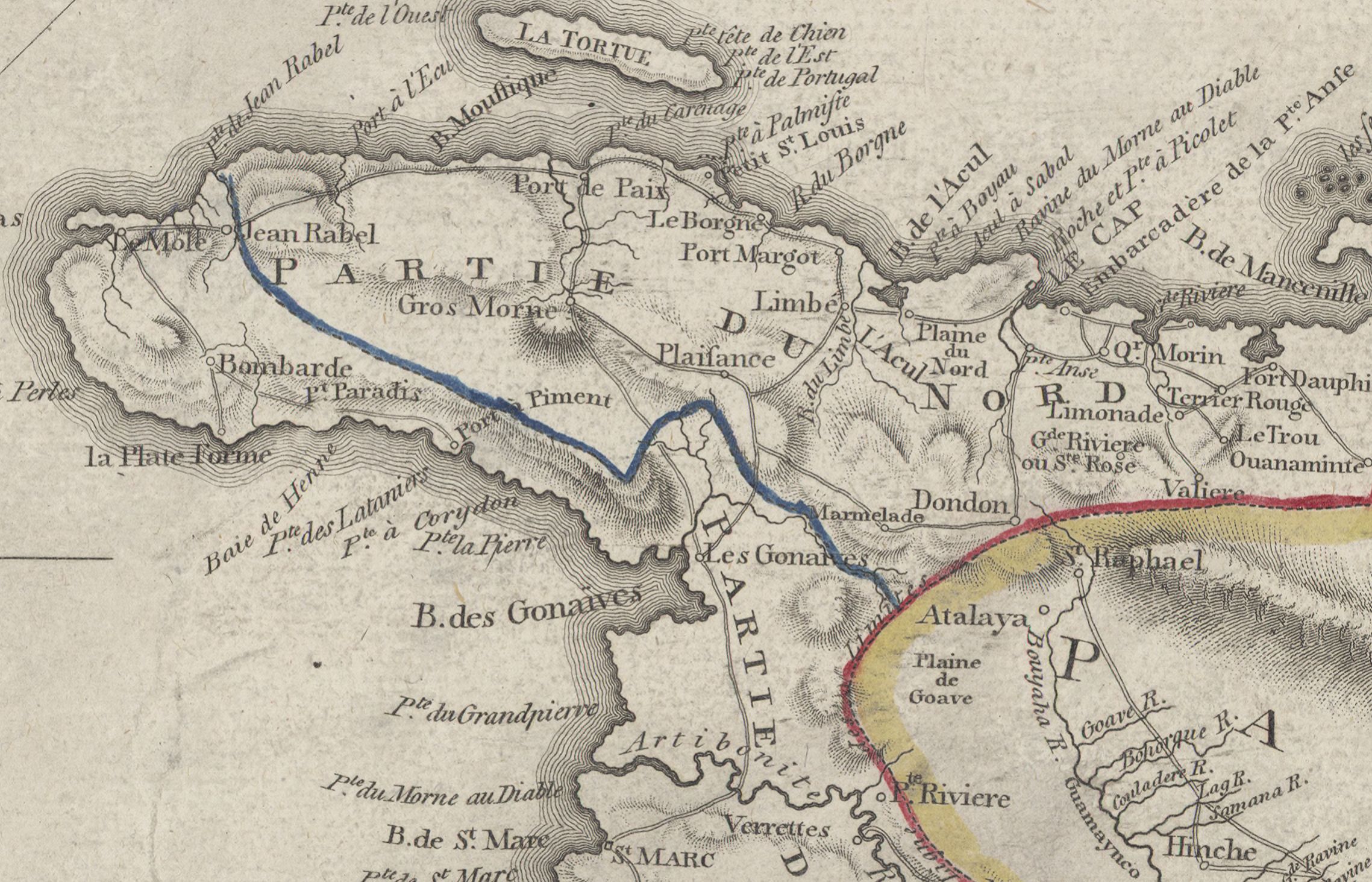

Saint Domingue

In 1793, the colony of Saint Domingue was riven with conflicts – conflicts over political change, abolition, and the rights of free citizens of color guaranteed under French law. Claude de Barras, Adélaide Sarba, and their eight children lived at the very center of these conlicts. Claude de Barras owned slaves, Adélaide Sarba and their eight children were people of color, and nobody in the colony seemed capable or confident of finding a peaceful political path forward.

The fighting in Saint Domingue began in earnest in the fall of 1790. The Declaration of the Rights of Man in the fall of 1789 granted equality to all French citizens, dividing the colonists. The elected representatives of the General Assembly of Saint Domingue in Saint Marc refused to recognize the rights of free people of color, people like Adélaide Sarba and at least one of her children. The government responded slowly, which led to the insurrection in October, 1790, led by mulâtre Vincent Ogé in the north-eastern part of the colony, where Claude de Barras and other Géricault relations owned plantations .

Vincent Ogé was captured in November, 1790, and executed early in 1791. Six months later a much larger rebellion broke out when people of color of all castes set much of the northern plains aflame. The violence persisted through 1792 and 1793, interrupted by periods of uneasy peace. In August of 1793, Claude de Barras was likely right to be concerned about the posterity of his children with Adélaide Sarba, whose rights by then had been fully recognized by the authorities over the passionate objections of many white colonists.

Paris

Claude de Barras died in Paris on January 24, 1807, as noted. We do not know how or when he made his way there from Saint Domingue. Many of his surviving Saint Domingue relations were present, or represented, at the meeting held in the family apartments at n° 9 rue de la Concorde the following May to determine his succession. Claude’s sister Marie Anne Charles de Barras, her husband Louis Robillard de Péronville and their daughter Zoe lived at the same address. Claude may well have lived in Paris as part of this family. Claude’s sole surviving brother Étienne de Barras was not present or represented, a notable absence, although Étienne’s name does appear in his brother’s papers. No reference to Adélaide Sarba appears anywhere in these documents.

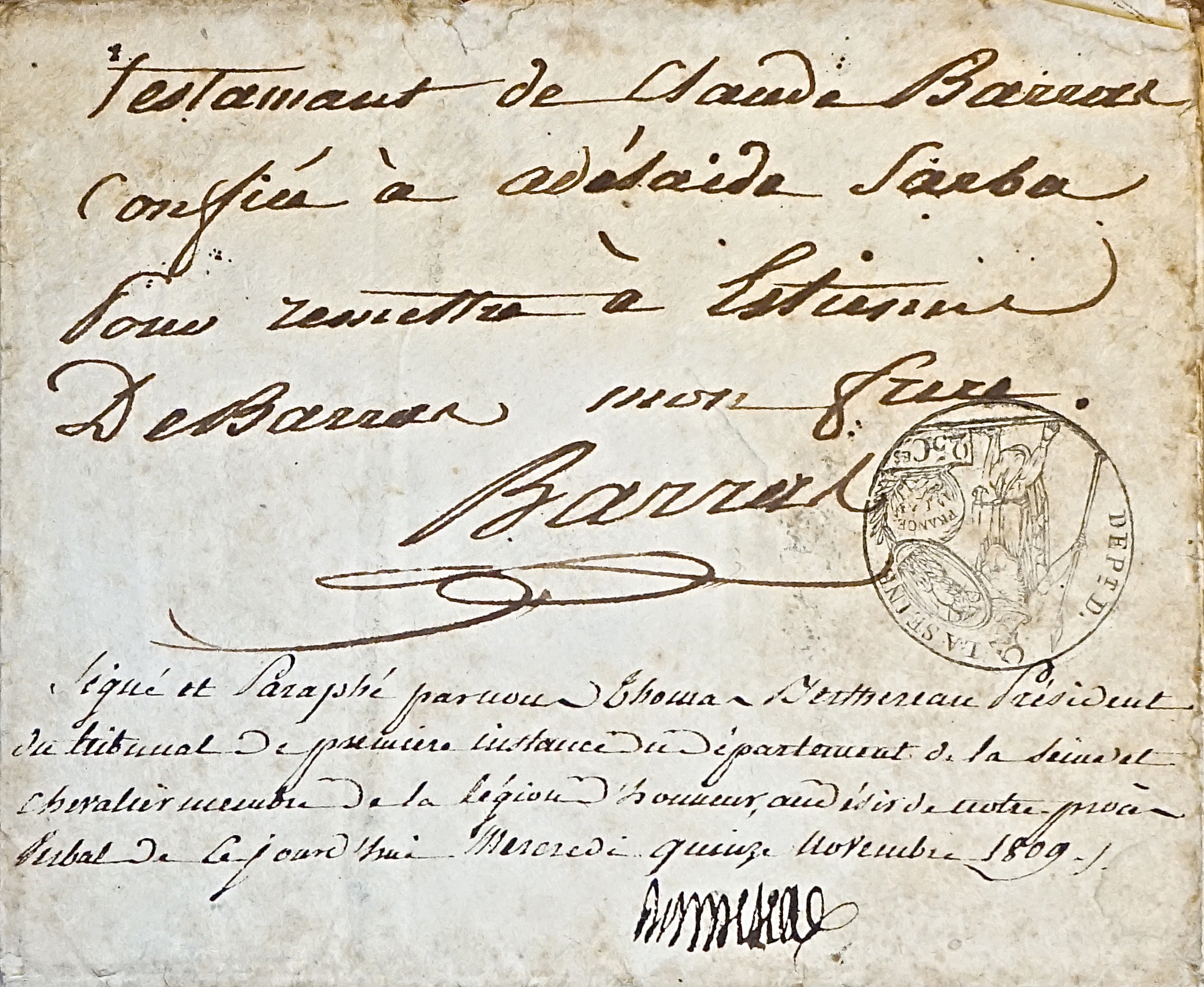

On November 15, 1809, however, Étienne de Barras did appear in Paris – at the Palace of Justice, where he presented a sealed envelope containing the handwritten will his deceased brother Claude de Barras composed on August 21, 1793, at the plantation of Louis Robillard de Péronville, his brother-in-law, in Champagne, quartier du Borgne, Saint Domingue, to the tribunal of the first instance (a civil court) of the municipal government.

Testament Olographe de M. Claude Barras – 1793

Dépot de Testament Olographe de M. Claude Barras (envelope front) 15 november 1809, notaire Delacour MC/ET/XIX/935. Image courtesy of the Archives Nationales (France).

Thomas Berthereau, President of the tribunal of the first instance du Département de la Seine and his colleagues in Paris examined the envelope and its contents and judged the 1793 will of Claude de Barras to be authentic. These documents were then turned over to the notary Alexandre Delacour to be preserved among his records.

The handwritten will of Claude de Barras runs to three pages. In this, our initial discussion of the document, we will focus on the first part of the will and the information pertaining to Adélaide Sarba and their children. This is the only document in the notarial records we have been able to locate which makes any mention of Adélaide Sarba and her children.

Dépot de Testament Olographe de M. Claude Barras (page 1 detail) 15 november 1809, notaire Delacour MC/ET/XIX/935. Image courtesy of the Archives Nationales (France).

“premier page./. au Champagne quartier du Borgne sur l’habitation de Monsieur Robillard de Péronville, le Vingt un, du mois d’août Mille Sept cent quatre vingt treize. Etant sein du corp et D’esprit voulant, avant que Dieu dispose de mes jours, disposer de mes dernieres volontes. Je nôm pour mon Executeur testamantaire et pour mon Legataire universelle la personne de mon frère Étienne De Barras. Je donne à mes Enfants naturelles isus d’Adélaide Sarba, les dits Enfants dans ce moment aux nombre de huit, la moitié de l’habitation que j’ai en société avec M. Geneve à la grande riviere de Jérémie, c’est a dire les cinquante quarreaux de terres…”

As noted, Claude de Barras prepared his will at the plantation of Louis Robillard de Péronville in Champagne, in the quartier du Borgne west of Le Cap on August 21, 1793. Claude first names his brother Étienne de Barras as his executor. He then bequeaths to his “natural children by Adélaide Sarba, the children at this moment numbering eight, the half of the plantation he owned jointly through an act of société with Monsieur Geneve at la grande rivière de Jerémie, that is to say fifty quarreaux of land (about 160 acres)…”

Elsewhere in the will, Claude de Barras asks his brother Etienne to look after the needs of Adélaide Sarba and their children, and wills the bulk of his estate to his Villette nephews and nieces. The will contains other interesting facts about Claude’s relations with other individuals, including creditors. At this point, however, we wish only to confirm the existence of Adélaide Sarba, the paternity of Claude de Barras, and the property bequeathed their children. The record of baptism of one of Adélaide’s children in 1786 tells us more.

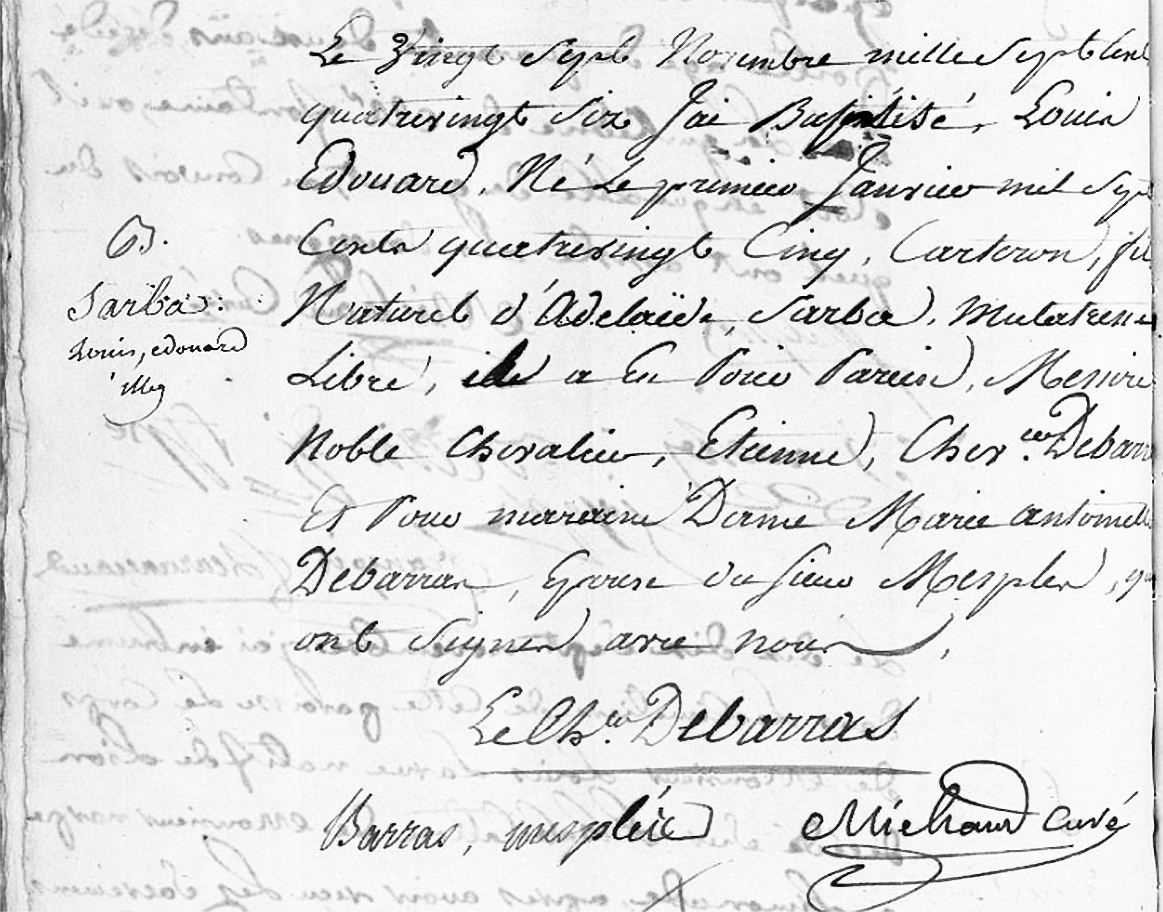

Baptême: Louis Edouard Sarba

Carte topographique de la région du Cap-Français et du Fort-Dauphin, au Nord-est de la colonie française ou St. Domingue – 1760 (Detail – Limonade – north east). Image courtesy of Gallica.

This record (below) confirms that Louis Edouard Sarba, the natural son of Adélaide Sarba, was born on January 1, 1785, and baptized in Limonade in north-eastern Saint Domingue on Novemer 27, 1786. As such, Louis Edouard was the nephew of Marie Anne Charles de Barras and Louis Robillard de Peronville – and of Claude’s other siblings and their spouses. We do not know the names of Louis Edouard’s brothers and sisters.

Louis Edouard’s act of baptism establishes the legal status of Adélaide Sarba at that time, as well his own. The document also provides additional important details which help us better understand the position of Adélaide Sarba and her children within the de Barras family in 1786.

Baptême Sarba: Louis, Edouard illeg, 27-11-1786, Saint-Domingue, LIMONADE, p. 7. ANOM, état civil, Image courtesy of the Archives Nationales (France).

The sacramental record identifies Louis Edourd cartoron as the natural child of Adélaide Sarba mulâtresse libre and his baptism by the curé Michaud on November 27, 1786, as well as his birth on January 1, 1785. A cartoron was the term employed to identify a male of one-quarter African ancestry. A mulâtresse libre identified a female of one-half African ancestry. The Chevalier Étienne de Barras and Dame Marie Antoinette de Barras, both siblings of Claude de Barras (and Marie Anne Charles de Barras) are named as godfather and godmother to Louis Edouard Sarba.

Étienne de Barras, we have already introduced. Marie Antionette de Barras is an interesting individual in her own right, as is her husband François Mesplès. We will continue our discussion of these individuals and other members of the de Barras family in Saint Domingue elsewhere.

The presence of the Chevalier Étienne de Baras and Dame Marie Antoinette de Barras as godparents to Louis Edourd Sarbre, in 1786, further supports the evidence present in the will Claude composed in 1793 – namely that during this period of time Adélaide Sarba and her children were valued, but publicly unacknowledged, members of the extended de Barras family.

Conclusion

Théodore Géricault’s connections to life in Saint Domingue, Claude de Barras, Adélaide Sarba, and the children they produced, were not based on family, although such ties do clearly exist, as much as they were on physical proximity and common experiences – in family homes and places of work and play in Paris, ties deepened at dinners and family celebrations over time, and cemented in shared social and financial interests. Géricault’s family in Paris was connected with their Robillard relations living at the Hôtel de Longueville, and with the Robillard de Péronville family on the rue de la Concorde, in multiple ways.

The text account of the existence of Adélaide Sarba, her relationship with Claude de Barras, and their eight children crossed the Atlantic to France with Étienne de Barras sometime before November, 1809, and disappeared into the records of notary Alexandre Delacourt. These individuals lived on in the memories of all who knew them, or of them. Marie Anne Charles de Barras died in 1837 1839. She and other family members carried the memories of Adélaide Sarba and her children across the Atlantic and into their homes in France and Italy. A contemporary witness wrote of watching Géricault as a youth of fifteen or sixteen speak caraïbe, the language of the Caribbean, publicly before his friends.

Géricault’s art suggests a strong personal interest in the lives of the forgotten and abandoned, and of those fighting for freedom, equality and justice. The discovery of Adélaide Sarba and her children is, for me, a bell which cannot be unrung – like learning of the existence of Claude’s brother, the naval hero André Edmond de Barras la Villette, who fell fighting for France in Sierra Leone in 1779, and who we introduced in our January issue.

These new discoveries, considered together with what we already know, force us to revisit many of our ideas about Géricault and his art, his masterpiece the Raft of the Medusa above all. Understanding better the identity of Théodore Géricault’s’ distant relations in the Antilles – struggling for equality under the law, reaping the rewards of slavery – and fighting for France’s colonial rights against the English off the coast of Africa, can we separate cleanly Saint Domingue and Sierra Leone from Senegal, or family from strangers in the Raft of the Medusa – the socially and politically provocative canvas Théodore Géricault presented to the public at the Salon of 1819? We will examine this question, and others, as we learn more about Géricault’s Saint Domingue relations and their lives in our next article.

* François Grenier (de Saint Martin) is an artist who has yet to be identified as follower of Géricault in any study I can locate.

Carte de l’isle St Domingue dressée pour l’ouvrage de M. L.E. Moreau de St Mery 1796 (detail). Image courtesy of Gallica.

* Article edited October 21, 2022 to accomodate the likely possibility that Adélaide Sarba and some of her children may have been slaves of Claude de Barras, or othe members of the de Barras family, prior to her manumission. The name ‘Sarba’ is likely an anagram of Barras. Freed slaves often found themselves with family names of their former owners a this time. Many thanks to regular reader Marijke Jonker for her keen eye, scholarship, and constant support.