1810 – La chambre ardente de Virginia Parker

Géricault Life

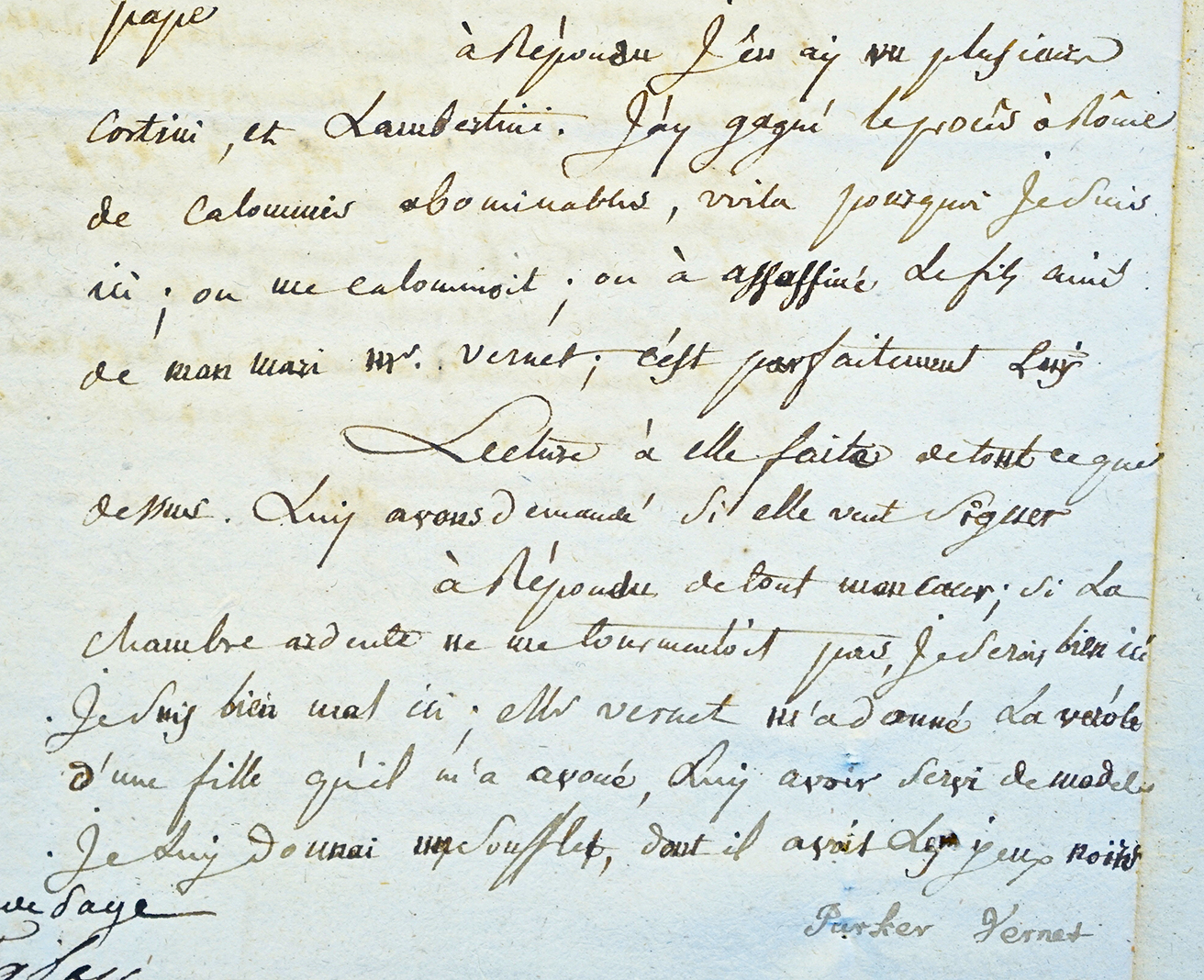

Procès-Verbal d’Avis Pour Interdiction de La Demoiselle Veuve Vernet (Virginia Parker) – February 23, 1790, (detail), Y//5187/B – Archives Nationales (France)

Virginia Parker – Madame Vernet

Virginia Cécile Parker, the mother of Carle Vernet – Théodore Géricault’s teacher from 1808, and the grandmother of Horace Vernet, Géricault’s lifelong friend, died in a maison de force (mental hospital) on the rue de Bellefond in Paris on November 17, 1810. Virginia had been confined in apartments on the third floor of the maison des Demoiselles de Douay (Douai) for more than twenty years. Virginia was placed in this mental hospital/prison for women at the request of her husband Joseph Claude Vernet, best known for his paintings of the ports of France.

Virginia was the daughter of Irish naval officer in the service of the Pope. Virginia Parker met her future husband while Joseph Vernet was studying and painting in Italy and married in 1745. The couple had three children: Livio, Félicité, and Antoine Charles (Carle). Virginia’s mental health reputedly began to break down after the family relocated to France. Unable to find doctors capable of helping Virginia recover, Joseph Claude had Virginia confined.

Joseph Claude Vernet died late in 1789. By this time, Joseph Claude had been living in the Galeries du Louvre in the Tuileries for some years and Virginia Parker had been placed in the maison des Demoiselles Douay on the rue de Bellefond. Virginia Parker, at the request of her family, was interviewed by Antoine Omer Talon, lieutenant civil au Châtelet de Paris, in order to assess the state of her mind in February, 1790. Virginia’s responses to the questions posed in this interview are disturbing and fascinating. We present the main thrust of Virginia’s responses transcribed by Jules Guiffrey in 1893* and then provide commentary below.

… La Chambre Ardente (The Flaming Room, Burning Chamber)…

“…dame Vernay, laquelle étoit vétue en déshabillé blanc et un bonnet sur lequel étoit un ruban noir. A elle demandé ses noms, âge, et qualité? A répondu: Parker, je suis mariée a M. Vernet, peintre du Roy; il y quinze ans que je suis ici. A elle demandé qui l’a mis ici? A répondu: le Roy, la chambre ardente A elle demandé: De quoi est composée la chambre ardente? A répondu: Vous ne pouvez pas ignorer tout cela, on me tourmenté; je suis née à Rome; je croyais le pape souverain; voilà comme j’étois. Il n’y a que cinq ans que je sais les affaires d’Etat, la chambre ardente m’a mis au fait de tout cela. A elle demandé: Si elle a vu la chambre ardente? A répondu: Non, je serois curieuse de savoir comment ils font pour tourmenter les têtes. A elle demandé: Si elle a vu le pape? A répondu: J’en ay vu plusieurs, Corsini et Lambertini. J’ay gagné le procès à Rome de calomnies abominables, voilà pourquoi je suis ici, on me calomnioit, on a assassiné le fils ainé de mon mari M. Vernet, c’est parfaitement luy…” (* see below: p. 98)

“Dame Vernay, (entered) dressed in a white housecoat and cap adorned with a black band. When queried about her age and status, Virginia provided her own name; declared herself marrried to M. Vernet, the kings’s painter; and resident ‘here’ for fifteen years. When asked why she was placed ‘here’, Virginia offered two causes: the king and la chambre ardente. When asked of the composition of la chambre ardente, Virginia replied: you cannot ignore everything here, I am being tormented; I was born in Rome; I believed the pope my sovereign; that’s how I was. By the time I was five years old I knew how governments work, la chambre ardente taught me all that. When asked if she had ever seen la chambre ardente, she replied no, I would like to know how they are able to get inside our heads. When asked if she had seen the pope, Virginia replied I have seen several, Corsini and Lambertini. In Rome I won trials when abominably slandered, that’s why I’m here, I was slandered, they killed the eldest son of my husband M. Vernet, it is perfectly him…”.

The meaning of Virginia Parker’s comments would be difficult to determine even if had we a more complete picture of the interview and information from her caregivers. We will provide commentary. We first provide Guiffrey’s account of Virginia Parker’s concluding remarks and then the actual document (end of one page; beginning of another).

… M. Vernet m’a donné La verole…”

“Lecture à elle faite de tout ce que dessus luy avons demandé si elle veut signer A répondu: De tout mon cœur, si la chambre ardente ne me tourmenttoit pas, je serois bien ici. M. Vernet m’a donné la v — d’une fille qu’il m’a avoué luy avoire servi de model. Je luy donnai un soufflet, dont il avoit les yeux noirs. Je dis la vérité; ils s’est guéri en cachète, cela est bien mal. Je luy ay donné des soufflets, il m’a donné la v— Et a signé cy contre: Parker Vernet.”

Procès-Verbal d’Avis Pour Interdiction de La Demoiselle Veuve Vernet (Virginia Parker) – February 23, 1790, (detail), Y//5187/B – Archives Nationales (France)

“Reading to her everything written above. We asked her if she would like to sign it. Virginia responded: With all my heart, if the fiery room did not torment me, I would be fine here. M. Vernet gave me la vérole, from a girl he confessed to me had served as a model. I gave him a slap, which blackened his eyes; he healed in secret. I speak the truth; it healed in secret, which is very bad; I gave hims slaps, he gave me la vérole. Parker Vernet. and signed opposite.”

Commentary

The two most importent terms: la chambre ardente and la vérole appear here in the original French to allow readers to form their own opinions of Virginia Parker’s responses. Before we begin to unpack the possible meanings of her responses, some context may be of use. Few words better capture the prison of suffering the mentally ill experience than la chambre ardente – the flaming room. The main historical use of la chambre ardente refers to the treatment of heretics during the reign of Francis I and, to a lesser degree, a trial of poisoners.

Both historical references and the metaphoric reference resonate with Virginia Parker. Her mental difficulties were well known during her life, evidently. Two particular stories circulated, both dealing with a phobia of being poisoned, naturally by accident, or for some sinister purpose. Virginia would demand her bread be purchased from a different bakery each day, and also had her water drawn from the center of the Seine – neither practice a bad idea given the hygene of the times. The water of the Seine was famously injurious, even to the healthy.

Obviously, we cannot know what Virginia Parker was thinking at any point in her life. Yet we would probably be wrong to believe Virginia Parker incapable of referencing the chambre ardente as a metaphor for her own current difficulties. We know from Charles Blanc’s biography of Carle Vernet, Virginia’s son and Géricault’s teachers, that Virginia Parker and Joseph Claude Vernet moved amidst leading enlightenment philosophes including Voltaire. Virginia at the very least had to be literate in order to reference the term la chambre ardente whether figuratively, or literally. As for Virginia’s claim that her eldest son had been killed, was she referring to a miscarriage, a real event, or pure fantasy?

As for la vérole, syphilis was a major problem throughout Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries. Virginia Parker was clearly prepared to publicly accuse her husband of contracting la vérole from a model and passing the disease on to her. We are in no position to assess the veracity of Virginia Parker’s account of Joseph Claude Vernet’s confession. Nor can we determine whether Virginia Parker in fact contracted syphilis, or any other disease, from her husband or any other source.

Conclusion

Untreated mental illness, madness – aliénisme, folie – as well as fidelity and faith are some of the undercurrents pasing through our examination of Théodore Géricault and his art. The status of women in French society is clearly also an important issue within Géricault’s circle, whether we are talking of the exlusion of Bonne Emilie de Nanteuil from her husband’s will, or the confinement of Virginia Parker. Mental illness we know now was a fact of life in Géricault’s family. François Louis Caruel, Géricault’s uncle, was very nearly committed to a maison de force by his own parents. The care and treatment of the mentally-ill had for centuries been mainly the responsibility of the church. That practice was changing late in the 18th century. Géricault, we know, painted the mentally ill. A great deal of evidence, including the confinement of his own grandfather before his birth, and that of the grandmother of his friend Horace, during Géricault’s life time, confirms that Théodore’s interest in the treatment of the insane was far from academic.

Carle Vernet and his wife Fanny Moreau must have visited Virginia Parker in her apartments on the rue Bellefonde. Horace Vernet, their son, likely made similar visits to his grandmother’s apartments. Charles Blanc asserted that Carle Vernet was mocked during his lifetime for his ostentatious faith in the catholic church. We forget too easily, perhaps that Carle seriously considered entering religious orders for a time. Ultramontanism, making the pope sovereign, was and is an importtant force in cathoic Christianity. Virginia Parker was clearly familier with the philosophy. Her remarks suggest she had little respect for the pope at the time she was interviewed.

The Inventaire après le décès de Madame Vernet, (1810 déc 21 Archives nationales, MC/ET/LVI/527) suggests Virginia Parker lived simply. She kept three paintings in her apartments on the third floor of the Demoiselles Douay: each a portrait of one of her children. How tortured, or ill, was this intriguing woman? We are left with questions and few answers. Was she really mentally ill, and if so how severely? Did syphilis play a part in he mental illness? How unhappy was Virginia Parker? Was the chambre ardente a true and accurate portait of her mental state? Did Virginia believe herself persecuted tormented, slandered, and confined without cause? The answer to this question must be yes, at least to some degree. Yet, despite her absence from the salons and parties, and even from the histories of her son and grandson, Virginia Parker, was always present in the minds and hearts of those who cared for her, but were powerless to free her from her prison on the rue Bellefond. Virginia Parker also has place in our study of Théodore Géricault an individual who clearly struggled at different stages of his life with demons of his own.

Portrait of Virginia Parker – 1767 Van Loo, Musée Calvet

* One can read the complete transcription of the “Procès-Verbal d’Avis Pour Interdiction de La Demoiselle Veuve Vernet” in Jules Guiffrey’s Appendix to “Correspondance de Joseph Vernet Avec le Directeur des Bâtiments sur la Collection des Ports de France, et avec d’autres personnes sur divers objets 1756-1787” (highly recommended) in the Nouvelles Archives de l’art français Series 3, Volume 9, 1893 here.