Filhol – Engravings

Géricault Life

St. Jean Baptisant Sur Les Bords du Jourdain, plate 1, livraison 1 of Antoine Michel Filhol’s 1802 Cours Historiques et Elementaires de Peinture ou Galerie Complette du Museum Central de France.

Filhol, Landon, and the Musée français.

The engraving above is of a painting by Nicolas Poussin: St. John Baptising on the Banks of the Jordan which Antoine-Michel Filhol, an engraver active in Paris, selected as the first for his Cours Historiques et Elementaires de Peinture ou Galerie Complette du Museum Central de France (An Elementary and Historic Course in Painting, or the Complete Gallery of the Central Museum of France), which Filhol began publishing in the summer of 1802. Théodore Géricault’s relations Louis Robillard de Péronville and Pierre Laurent began publishing their own engravings of the national collection – entitled the Musée français, in the spring of 1803. (See our earlier issues.) Charles Paul Landon began publishing engravings of pieces from the national collection in his Annales du Musée, in 1801. I discuss Charles Paul Landon’s Annales du Musée elsewhere in the current issue.

Educating the Public

As the title suggests, Filhol’s Cours Historiques et Elementaires de Peinture ou Galerie Complette du Museum Central de France was explicitly didactic in nature. Each of Filhol’s livraisons featured six engravings: five of paintings, and one of a piece of sculpture from the national collection, plus commentary. Filhol hired top artists and engravers, however, and clearly strived to produce high-quality engraving designed to appeal to discriminating and affluent consumers.

Engravings and prints, or estampes, played a vital role in every level of French society during the 18th and 19th centuries. Stalls selling prints can be found along the Seine today, and were a fixture of Parisian life in Théodore Géricault’s day. Filhol’s Cours Historiques et Elementaires de Peinture ou Galerie Complette du Museum Central de France was clearly aimed at a more upmarket consumer – those more likely to frequent the shop of a marchand de tableaux, where paintings and quality engravings of high quality were offered for sale. In late 1804, Filhol’s Cours was retitled as the Cours Historiques et Elementaires de Peinture ou Galerie Complette du Musée Napoléon.

Our purpose in our first article on Filhol is to introduce his engravings, and to provide a sense of his mission, as it were. To do so we begin with a brief examination of the extended commentary which accompanied the plates of the cours.

As we noted in our discussion of Landon, Landon’s emphasis is on the science of art and architecture. Filhol does the same, yet situates his efforts explicitly within a biblical context: dividing history of the arts into two epochs – before and after the flood.

The images below are from volume 1 of Filhol’s 1802 edition.

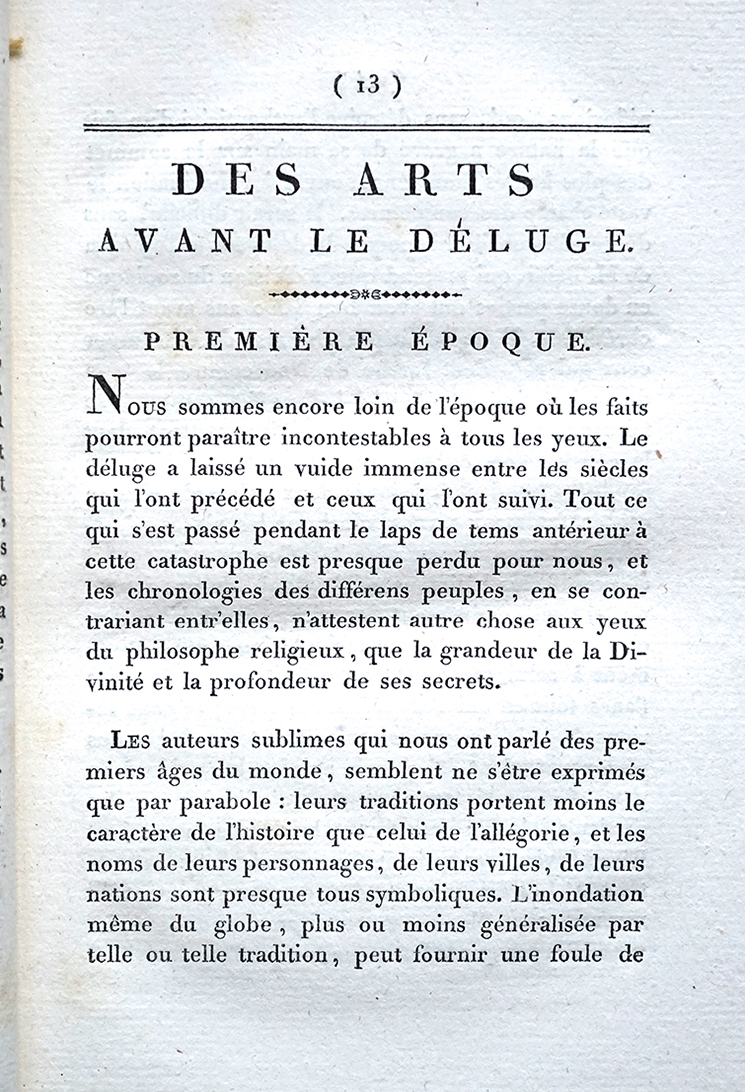

Arts Before the Flood – First Epoch

First page of the essay: Des Arts Avant le Déluge in Filhol’s Cours Historiques et Elementaires de Peinture ou Galerie Complette du Musée Central de France Paris, Chez Filhol, Artiste-Graveur et Editeur, rue des Francs-Bourgeois St. Michel, n.° 785. De l’Imprimerie de Gillé Fils. An X – 1802 (Private Collection)

Conclusion

“…Le déluge a laissé un vuide immense entre les siècles qui l’ont précédé et ceux qui l’ont suivi… (…The deluge left an immense void between the centuries which preceded and those which followed it…) The discourse on art before and after the flood may or may not be of interest to modern readers.

What is telling about Filhol’s discourse is the absence of critical debate about biblical authority at this point in French history. The science of Landon’s Annales draws on the Institute studies conducted by French scientists. (the Institute was France’s new Academy.) Science and industry were vitally important in France and elsewhere at this time. Yet, despite discussions in France and abroad regarding the age of the earth, etc., these discussions occured within domains often bordered and defnined by biblical history as fact.

The second part of Filhol’s commentary resembles many histories of the time, the rise of civilizations, etc. confounded by conflicts with savages and barbarians of various stripes. Understanding historiography of this type is vitally important because these arguments set the stage for nineteenth-century scientific racialism, the science of phrenology, and the art and culture which emerged during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Filhol’s commentary, therefore, reminds us that Géricault lived during a time of dramatic change of all types.

In subsequent issues we will examine more examples of Filhol’s work, and consider the role the state played in sponsoring publishers like Filhol, and Géricault’s relations Louis Robillard de Peronville and Pierre Laurent. What we hope to make clear is that prints were very much part of everyday life, and were produced across Europe for a thriving market of consumers from almost all social ranks. Any citizen could view the national collection. Filhol’s livraisons permitted everyone to become something of an expert whether one lived in adjacent to the Museum Central des Arts or in some distant land. Visitors could study the engragings, and absorb the accompanying commentary, as we shall see. We shall examine how Filhol’s engravings compared with those of Landon, and Géricault’s relations, Louis Robillard de Peronville and Pierre Laurent.

Yet, whether we wish to push such considerations aside or not, discussions on many topics took place in a world in many ways still defined and understood in biblical terms. In this world, should we attach any significance to Filhol’s decision to make St. John Baptising on the Banks of the Jordan the first plate of his series? What did Géricault and his peers, raised in a largely de-christianized France, make of the history of art defined often in biblical terms, in world where some, at least, accepted biblical truth as fact?

Arts After the Flood – Second Epoch

First page of Des Arts Après le Déluge in Filhol’s Cours Historiques et Elementaires de Peinture ou Galerie Complette du Musée Central de France Paris, Chez Filhol, Artiste-Graveur et Editeur, rue des Francs-Bourgeois St. Michel, n.° 785. De l’Imprimerie de Gillé Fils. An X – 1802 (Private Collection)