Balls Fêtes – Hôtel de Longueville

Géricault Life

1700 Couvercle de clavecin double... (detail) Musée des arts décoratif Paris.

Introduction

The balls and fêtes held at the “Maison Longueville” from 1798 were well attended and enjoyed an international notoriety. In our first discussion of this form of culture and commerce at the Hôtel de Longueville we examine two contemporary accounts – both of which illuminate the world of Théodore Géricault as a youth in Paris. Commentary follows.

Charles Henrion’s description of the “Bal de l’Hôtel Longueville” was one of the primary sources for 19th-century historians of Paris life under the Directory but very rarely appeared in its entirety. Henrion’s sharp observations of French society under the Directory are similar to those of Carle Vernet, Géricault’s teacher, and other observers who grew up immersed in the satire and irony of the 18th-century.

Controlling public and private celebrations figured prominently in the plans of a succession of administrations. Indeed, administrators in Paris imposed a variety of restrictions on dress codes and hours on private balls in the closing years of the 18th-century. Needless to say, the populace rebelled against these restrictions in various ways. One such rowdy outbreak at the Hôtel de Longueville required the intervention of the police. The expulsion of guests no doubt enhanced the notoriety of the balls at the “maison Longueville” in the public eye. We can only speculate what the family of Géricault in Paris made of such displays.

Henrion – Ball de Longueville – 1799

“One dances everywhere in Paris; we danced upon the ruins of the Bastille, still damp with the tears of victims which it once held; we danced upon the tomb of the Boutins at the modern Tivoli: we danced in the churches, suddenly transformed into bacchante halls…One dances everywhere, and the storehouses of this great city are filled again with necessities; one dances everywhere, as insurgents rage in the departments of the West; one dances everywhere, as we make war against all Europe; one dances everywhere, and three hundred thousands fighters depart from the bosom of this great city…O Paris!

I was at the Ball of the Hotel Longueville in a salon as majestic as the gallery du Louvre, where we become lost in this great space; where thirty clusters of sixteen dancers wheel and circle, for we do not dance as eight there, as our fathers did. Three hundred women swirl like waves sweeping and moving together. One wears an elegant hat of pink satin, glistening with luminous snowflakes from the studios of Wenzell; others choose hats adorned with an artistically placed feather, the tip may touch a roguish eye, or grace an ear attuned only to the language of love. Others dress in small bonnets called à la Paysanne. A simple undergarment and veil of modest gauze alone keeps them cool. The unpretentious covering not only embellishes the body, but identifies the wearer as a rose of modesty, or lily of innocence….Who are these small, giddy fools with uncovered heads? Each is a kind of modern Titus or Caracalla, known now by the names Sophie or Ursule, and who are, without doubt, quite happy to simply count sighs.

The instruments resound, and the baton of Hullin gives birth to voluptuous curling waves, which roll one upon one another with the majesty of celestial bodies, or with the soft rippling of flowering prairie grasses, balanced by the Zephyr’s warm summer wind. The echoes of golden trumpets repeat, and with the prolonged accompaniment of horns syncopated in two measures, we are stirred by the moving sounds of the waltz.

Ah! without this harmonious music, we would hear only the cascade of sighs emanating from hearts blessed by the charms of these delicious women – whose sensuality is multiplied in magical mirrors reflecting a thousand graces, before a single feeling is actually produced. The young man is seduced, his heart beats faster, his senses are inflamed. He comes seeking happiness, and often does not find even pleasure.

Vast salon! Do you contain one hundred different peoples? No, I am never confused among your dancers, where the modest worker finely dressed on the decadi finds innocent release from her long labors, and the courtisan amuses herself with the puppet she bribes, and who deceives her. But these beings, so different, do not mingle their games; each dance is composed differently. Near the entrance, we find two quadrilles of negresses who are ignored by those who dance nearby, as with neighbouring peoples who never speak to each other, whose languages would first need to be translated to be heard.

During the carnival, these dress balls change into bals déguisés [costume balls]. On these occasions these same women, who normally drape themselves in gold and purple, go dressed as poissardes [women of the fish market], with a little blue peasant vest, and a red scarf for headwear. Many of these need do no more than wear their everyday clothes. For them, only the regular balls are costume balls.” (Encore Un Tableau de Paris Chapter 2: Bal de l’Hôtel Longueville, pp. 14-18, Paris: Chez Fauvre, An Huit, [1799-1800])

Bal masqué at the Maison Longueville

Journal Politique de l’Europe, (Faisant suite à la Gazette des Deux-Ponts.)

Du Dimanche 19 Mai 1799 (excerpt p. 505.)

___________________________________

“…The Pope arrived at Briançon on 11 floréal (30 April) at noon: he had for an escort 40 knights of Piedmont, some bishops and arch-bishops, and made part of the trip by sedan chair. He stopped at the general hospital. (Adds the Publiciste): He was accompanied by 40 people and he presented a superb figure there, but he suffers from a paralysis of his limbs. The prelates and abbots who accompanied him went to a mass of the constitutional clergy. It was said that the Pope was insulted by a jew [sic] in Borgo: the papers of this city claim that this is not exactly correct; and that the people had injustly accused this jew of irreverence towards his holiness, S.S.

Augustin Monneron, age 43, native of Annonay in the department of l’Ardeche, and former director de la caisse des comptes courans [an association of bankers], accused of bankruptcy fraud and of misappropriating banknotes of the caisse des comptes courans, was acquitted by the criminal court of the Seine the day before yesterday, upon the declaration of the jury.

At one in the morning, May 11th, agents of the police were called to the bal masqué at the maison Longueville to remove 200 individuals who refused to leave the premises…”

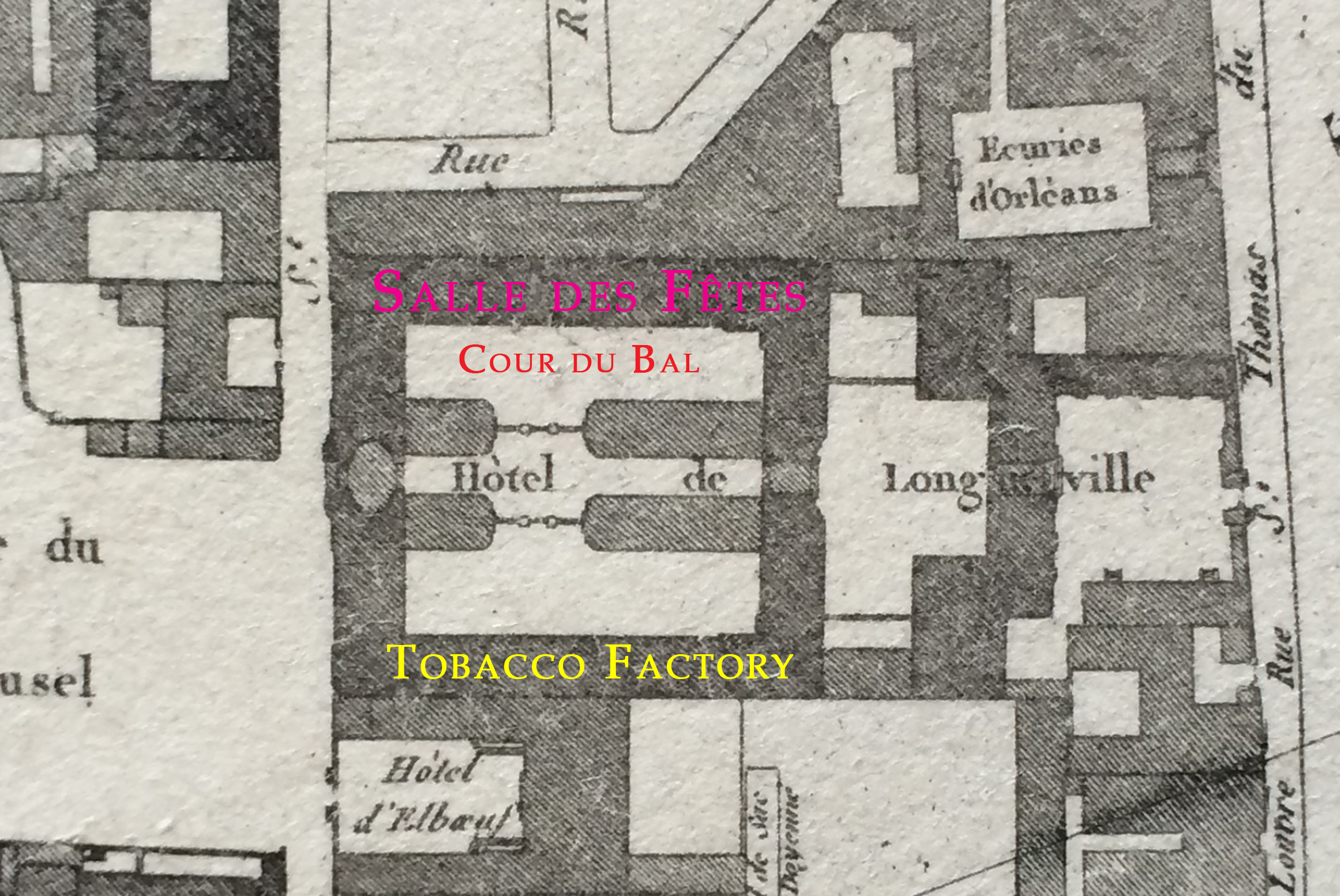

Salle des Fêtes (Ballroom), formerly Republican Wallpaper Manufactory, and the courtyard designated “Cour du Bal” from 1798. Map: 1790 Verniquet (detail)

Commentary

From 1791, members of Théodore Géricault family lived and worked Hôtel de Longueville. From 1797 at the latest, Géricault’s father worked at the family tobacco concern there. From 1800 until 1806, the Robillard tobacco concern founded by Géricault family members and others acquired complete control of the Hôtel de Longueville with all the obligations this lease of biens nationaux entailed.

The two short notices which precede the account are equally relevant to our examination of Théodore Géricault, however, and are included for this reason.

The first is general and touches on the status and treatment of the Pope, who many in France throughout the revoltionary period regarded as the legitimate heir to Saint Peter. Two older members of Théodore Géricault’s family held offices in the Catholic church.

Augustin Monneron was a close confederate of Géricault’s family in Paris, a former resident of the Hôtel de Longueville, and very likely a silent partner/founder of the original privated tobacco concern established at the Hôtel de Longueville by Géricault family members and others. His trial would have been of keen interest to a number of Théodore Géricault’s relations, the public in France, and select individuals abroad.