Géricault – Guillotine

Géricault Life

1819 Tête de jeune homme mort (detail) Théodore Géricault. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen.

Introduction

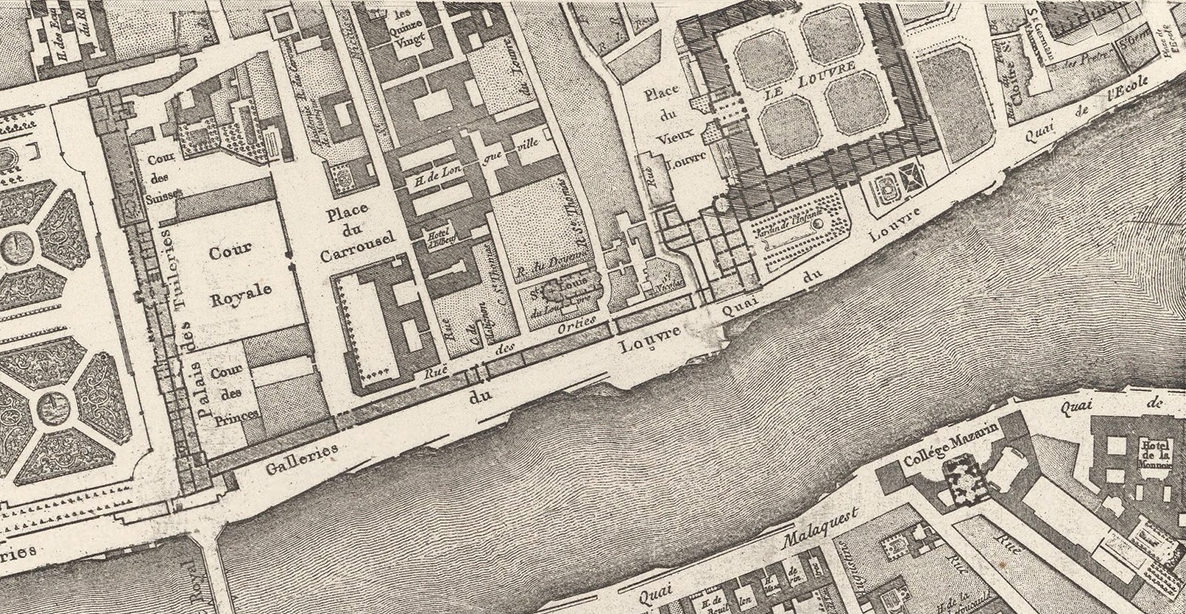

The Géricault family apartments in the Hôtel de Longueville overlooked the site of the battle of August 10th, 1792, fought at the Tuileries palace between troops loyal to the king and insurrectionists in Paris, and the subsequent massacre of the Swiss Guards. The guillotine was installed in the Place du Carrousel soon after and within days crowds gathered outside the Hôtel de Longueville to watch the taking of heads. Théodore Géricault’s first biographers report that his interest in violence and death marked the artist among his contemporaries. Gustave Vericel’s 1885 study of the installation of the guillotine in Lyon early in 1793 provides us with a sense of how different political factions regarded the instrument and its role in the public space.

Inventions

In 1792, a machine to painlessly and quickly end the lives of those convicted of capital crimes was installed in the Place du Carrousel opposite the Hôtel de Longueville, the site of the Géricault family tobacco business. Enterprising print sellers and wallpaper vendors Fillion and Valmont of Paris and Rouen quickly prepared engravings of the first execution in the Place du Carrousel to sell to the curious. The following February, in the Place de la Révolution in Paris, Louis XVI was “guillotined.” The execution captured the attention of the world. Interest in this new device soared, driving demand for more representations and models of the guillotine, demand which entrepreneurs in France and abroad did their best to satisfy and exploit. The subsequent trial and execution by guillotine of Charlotte de Corday and Marie Antionette, in particular, presented fresh opportunities for profit. Reproductions of these executions and of the “guillotine” appeared widely in a variety of media. By the end of 1793, the material fact of the machine’s existence was firmly established in the public imagination, and not just in France. Dr. Guillotin’s machine, born out of the physician’s efforts to reduce pain and suffering, had evolved into a cultural motif, a motif which seemed almost to have a life of its own.

Map: 1775 J.B. Jaillot (detail), courtesy of David Rumsey Maps.

In August of 1792, the guillotine was set up in the Place du Carrousel near the palace gates (Cour Royale). Political executions in the Place du Carrousel began in earnest in the spring of 1793. In early May the government moved the guillotine to the gardens on other side of the palace where the executions continued. Géricault family members had a front row seat for many of these, a topic we shall discuss further.

Lamp Post to Scaffold

The dismemberment and decapitation of Swiss Guards following the battle for the Tuileries palace of August 10th by an “outraged” citizenry was a dramatically larger instance of a not particularly common practice. Exagerating incidents of violence through the media, however, was common. We possess numerous images of citizens marching with decapitated heads on pikes and other acts of righteous barbarity, pre-1792, which amply illustrate this appetite for images of spontaneous violence, hangings, and decapitations. In early September, 1792, the “outraged” citizenry invaded the prisons of Paris and slaughtered those suspected of royalist sympathies in the September Massacres. These events and images naturally had a powerful effect upon the public imagination. Written records and images ensured that memories of these events survived long after and physically far from the actual events, thus making these incidents ideal subjects for monetization and propaganda.

À la lanterne! (To the Lamp Post!”) became the clarion call for violence against those profiting from the unjust exploitation of le peuple (the people) from 1788. In France, lanterns suspended from sturdy iron posts, usually mounted on stone walls, illuminated streets. Engravings and illustrations of priests and other malefactors hanging by the neck from lantern fixtures became standard motifs in depictions of spontaneous justice during this period. The invention of the guillotine, however, and the creation of political courts in March of 1793, restrained spontaneous violence and imposed the state monopoly on capital punishments.

During the first public executions in the Place du Carrousel, (re-named the Place de la Réunion) following the battle of August 10th, the guillotine glistened as a cypher, newly born and still free of meaning, a shining symbol of menace and death to some, and one of justice and even hope to others, as difficult as that may be to imagine today. How did this cypher acquire meaning? Through practice over time, of course; through discourse and re-tellings, and by the reactions of individuals and groups to the device as it stood in public view, how it was used, and how it evolved in the individual dreams and memories of the populace, an object in fact and and object imagined. Within months the device had acquired a potency closely linked with popular anger, justice/injustice, and death.

The presence of the guillotine and its place before the Hôtel de Longueville is confirmed in the press reports of the debates in the National Convention over the fate of Louis XVI in the fall of 1792. “…Had Louis XVI committed no other crime than being king, he would merit death…he was a monster encrowned, the guillotine awaits him in the Carrousel…” (Révolutions de Paris, N° 175, 10 au 17 Novembre, 1792, p.339)

In the months following the execution of Louis XVI the potency of this powerful symbol increased dramatically. The phrase à la lanterne! (To the lamp-post) gave way to La guillotine est là! (Literally “the guillotine is there!;”or, “there’s the guillotine!,” each translation a variant of the phrase used to describe the dire fate awaiting Louis XVI.) We can set aside the history of this trope for the moment, however. The immense number of prints and pamphlets discussing and depicting Dr. Guillotin’s device, and its victims, confirm the pervasive potency and resilience of the guillotine in the popular imagination and in media right up to the present day.

Public Display – Lyon

Royal efforts to eliminate the worst features of capital punishment throughout the realm meant that the departments of France would each have at least one instrument of execution in 1792. Gustave Vericel in his exhibition catalogue: Exposition Officielle de La Guillotine sur la place de la Fédération (Bellecour) ou Une Page de l’Histoire de Lyon en 1792. (Lyon, Librairie Générale Henri Georg, 1885.) described the fight which broke out in Lyon in late September, 1792, over the question of whether the guillotine would be a permanent fixture in the public square.

…on the 22nd of October, 1792, and during a meeting of the general council of the commune, a deputation from the central Society of the Friends of Liberty and of the Republic entered and demanded “that the guillotine sent to the city be displayed before the public to confound the enemies of the Patrie.”…

Nothing came of the incident, but four days later on the 26th of October, while the three administrative bodies met in the city hall that evening to discuss what measures to take to reduce the tensions in different cantons, the Commander-in-chief of the Battalion of Volunteers of Var, who was staying in our city, presented himself along with one of his officers and announced to the council “that he had been delegated by a great number of citizens from different sections who had taken up arms in order to once more demand that the guillotine, which had been taken the night and placed once more before the public remain in place on a Permanent basis, in the same way that guillotines in other cities of the Republic were permanently in public view.”

This was met by general cries of objection from the administrative officers present, who did not believe themselves obliged to leave the instrument of execution in the free hands of the People; they stated that they would not permit the guillotine to be placed before the public except to carry out executions ordered by the courts.

The Commandant of the Battalion of Var was little satisfied and resumed his demands… (Vericel, pp. 10-11.)

Vericel observed in 1885 that historians tend to make May 4th, 1793, the date when the guillotine became a permanent fixture in Lyon – writing:

The decree of March 20 1792 adopting a new method of execution had authorized the Executive Power to provide funds to ensure the method was uniformly adopted throughout the realm…Regarding Lyon, we have located no document which confirms the method or the date by which the the Guillotine arrived in the city…(Vericel, p.8)

Vericel then cites two authors who link the arrival of the guillotine in Lyon to Chalier, a Lyon administrator and ally of Robespierre and Marat. Vericel first quotes Aimé Guillon de Montléon from his Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire de Lyon Pendant la Révolution, Paris, 1824 (p.147).

…Chalier had received this instrument of death, until then unknown in Lyon, and in order to induce the terror which is was destined to produce, he ensured the machine be exposed straight away in the place de Bellecour: …first, to instill fear among the aristocrats of the nobility, and second to frighten the aristocrats of commerce… (Vericel, p.9)

Vericel then quotes M. Monfalcon from his 1851 edition of Histoire de la ville de Lyon, (p. 932).

…Chalier had ordered a new guillotine, [in the spring of 1793] by which he proposed to take five hundred heads, the machine would be displayed first at the place de la Féderation, then that of Liberty. Chalier ordered the instrument of death on his personal authority: he fought for a long time with the members of the courts, who wanted to keep the machine in the corner of the prison, as they had… (Vericel pp.9-10)

This second quote suggests the presence of two guillotines in Lyon, a real possibility. Vericel’s account of the confrontation of October 26th, 1792, and after, makes clear that leading figures in Lyon objected to publicly displaying the device on a permanent basis.

…the Assembly was deeply troubled, and was ‘constantly’ reminded by senior officers of the national guard that citizens of the sections had taken up arms and were preparing to march…The meeting room of the Council was already filled with armed citizens. The Commander of the Battalion of Var insisted again “upon the necessity of satisfying the people, by meeting a demand that did not to him seem at all extraordinary…” at the same moment, the citizen Bertholon, President of the central Committee and who was in the room, cried out that “the citizens who were assembling in different sections would not wait for the decision of the Administrative body to take their part, …”

It was then that, in a situation already deeply troubling, and in fear of greater horrors, that the vanquished Assembly declared “that it did not oppose any longer placing the guillotine in the place de la Féderation, inviting the municipal government to take all the necessary precautions to maintain public order and to ensure the public would not be troubled. (Vericel p. 14)

As Vericel notes, however, the mere presence of the guillotine in the public square on the night of October 26th and the following day during a time of spontaneous violence was enough to spur members of the public to action. They organized and signed a petition:

…and thus the Guillotine was officially and publicly established in the place de la Féderation in an act of surrender to the will of the People. The installation was successful but short-lived. On October 29th the three Administrative Corps, met again in the city hall to consider a petition signed by a great number of citizens demanding the removal of the guillotine. This is the text of this petition, and which has not been published before now… [We offer just a part.]

“…We submit to you today our reasons for removing this machine. It is destined to execute assassins and extreme malefactors, what of the mild and honest souls who this machine frightens?…it will make us all the guardians of the scaffold, a prospect which fills many among us with repugnance, and is a role we refuse to accept…” (Vericel, pp.17- 18)

Vericel notes with evident satisfaction that the petition carried the day. The guillotine was promptly removed from public view and secured in the prison of Roanne where it there remained and was used only to carry out court sanctioned executions – until July, 1793.

In accordance with this decision, the Guillotine was dis-assembled, and returned to its legal storage place, from which it would not emerge in any official capacity but for the [public] executions of Chalier and Ryard de Beauvernois…(Vericel, pp. 17-18)

Vericel concludes by noting that the public execution of Chalier and Ryard de Beauvernois helped trigger the violent reaction of the national government in Paris. Lyon was later subjected to extraordinarily severe punishments designed to inflict the maximum amount of pain and terror upon citizens actively hostile to politicians in Paris and local zealots.

Rituals of Revolutionary Executions

Republican government officials and their supporters were much concerned with the staging and rituals of execution, as we can see from the documents below, which provide contemporary reactions to the first executions, which took place during the spring of 1793 in front of the Géricault family residence at the Hôtel de Longueville.

“Rœderer to Guidon, May 13th, 1793”

“I enclose, Citizen, the copy of a letter from Citizen Chaumette, solicitor to the Commune of Paris, by which you will perceive that complaints are made that, after these public executions, the blood of criminals remains in pools upon the place, that dogs come to drink it, and that crowds of men feed their eyes with this spectacle, which naturally instigates their hearts to ferocity and blood.

I request you, therefore, to take the earliest and most convenient measures to remove from the eyes of men a sight so afflicting to humanity.” (from John Croker’s 1853 History of the Guillotine, p. 78.)

We see other concerns expressed in the Révolutions de Paris in the spring of 1793 by witnesses of the executions in the Place du Carrousel before the Hôtel de Longueville:

“We must put the finishing touches upon the guillotine; one could not imagine an instrument which better reconciles that which is owed humanity, & and that which the law demands; at least until capital punishment has been abolished. We must also perfect the ceremonial of the execution, & remove all which can belongs to the old regime. This cart which transports the condemned is that of Capet, these hands bound behind the back, which forces the condemned to adopt a bent and servile posture; this black robe with which the confessor may still adorn himself, irrespective of the decree which protects ecclesastical garb – all this costuming does not proclaim the morals of a nation enlightened, humane, and free. Perhaps, it is even impolitic to permit a priest to assist a counter-revolutionnary, a conspirator, or an emigré in his last moment. But the uplifting of religion can transport the criminal to confide matters of importance to a confessor disposed to impart it later.

Another reproach to make of these executions, is that, if wish to spare the condemned from pain, we must do more to keep the sight of blood from the spectatators; one sees it drip from the blade of the guillotine, & drench the ground below the scaffold; this repulsive spectacle should not be placed before the eyes of the people…

Does one not already hear the multitudes declare that the guillotine is already too gentle for the malefactors which have been executed to this point, & of whom several in fact displayed bravery facing death; do not the people degrade themselves in appearing to seek vengence in place of carrying out justice?” (Révolutions de Paris, N° 198, 20 au 27 Avril, 1793, pp.224-225.)

The guillotine was a permanant fixture of the Place du Carrousel/de la Réunion in the spring of 1793. By then, the National Convention was meeting in the former Tuileries Palace opposite the Hôtel de Longueville. The guillotine was in clear view. The guillotine operated in the Place du Carrousel until May 10th, when it was ordered to a new site in the Place de la Révolution, visible from the fashionable home of Pierre-Antoine Robillard and his wife Marie-Thérèse de Poix on the rue de Belle Chasse.

Gibbet to Guillotine

Our principal claim is that we should not underestimate the potency of images of death and of executions in the public imagination in France after 1793. The guillotine is only part of this fascination with death and suffering.

Vericel concludes his investigation into the permanent placing of the guillotine in Lyon with sharp observations linking the gibbet of the monarchy to the guillotine publicly displayed before the public. Both the gibbet and the permanent guillotine became integral fixtures within their particular situations, perhaps the most dominant fixtures of any public space in which they were placed.

The gibbet existed to terrorize ordinary people and criminals alike, with bodies suspended for days in full public view, often on a hill so that they would be visible to the citizenry and visitors from any vantage point. The gibbet in use was frightening enough. But it was equally frightening “at rest,” as it were, inactive for the present, but its very presence promising some future horror. The gibbet lived in the imaginations of the populace and was a feature of ghost stories and gothic romances. Despite the best efforts of moderate, or sensible, republicans, the guillotine evolved into something similar and equally frightening. The guillotine, too, lived in the imagination. La guillotine est là! How frightening might that phrase be to people living within a system dominated by leaders who declared the need for both terror and virtue.

We shall learn more about Géricault, the gibbet, and the guillotine when we shift our attentions to Rouen in the coming issue. The area of study is essential to our understanding of Géricault, an artist who grew up in a world where the gibbet, la lanterne, and guillotines were fixtures in fact, memory, imagination, and art.