Culture & Commerce (3)

Géricault Life

Image courtesy of the Archives Nationales (France) F/13/898 (Destruction – Signes – Féodalité. 1792-An 2)

The suspension of the monarchy after August 10th, 1792, and the enactment of laws suppressing symbols of feudalism challenged the status quo, to say the least. The intersection of culture and commerce remained; however, artists would either starve, or adapt. The image above is part of an invoice submitted to the government for the destruction of the “le soleil” (the sun) and armorial symbols, including the “fleur de lis,”above the rue Saint Nicaise entrance to the Hôtel de Longueville completed in early September, 1792. Different communities across France would react in different ways to these efforts to reconstruct the official face of France.

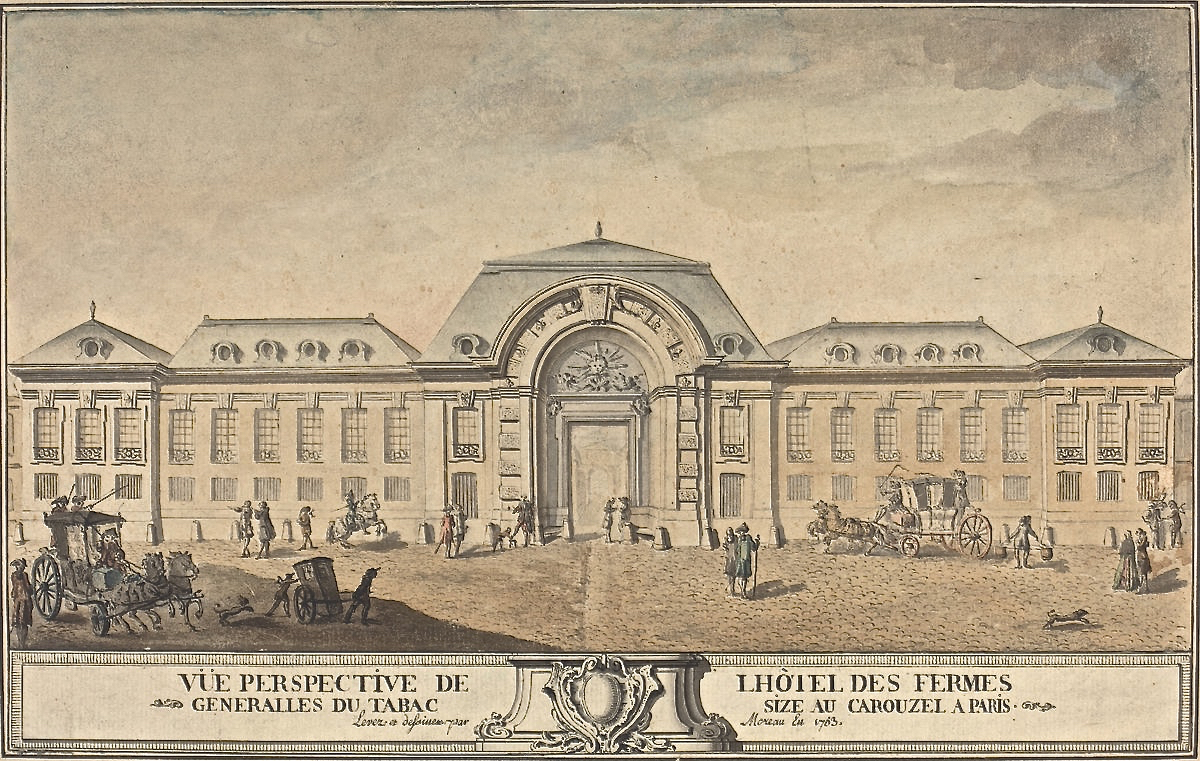

Hôtel de Longueville in 1763

Image by Moreau le Jeune, father-in-law to Carle Vernet, one of Théodore Géricault’s first teachers.

This is one of our most important historical images of the Hôtel de Longueville from the 18th century. The title and date confirm that the renovation work done after the Hôtel de Longueville passed into the hands of the tobacco tax farmers had already been largely completed. We thus can look at the building as Géricault family members did, and walk through the Passage Longueville to the site of the Encan Nationale, or stop midway and turn right to the family tobacco manufactory. The sun above the entrance would be hammered away by Citizen Armand and his workmen in the late summer of 1792. Duperon’s Republican Wallpaper Manufactory stood on the left. We know that Géricault’s uncle Jean-Baptiste Caruel occupied apartments overlooking the Place du Carrousel after 1800. We do not know whether he lived in these same apartments in 1792. These apartments would have been on the upper floors to the right. Brunton’s haberdashery was situated below.

In late August of 1792, and during the month of April, 1793, the guillotine would have stood immediately to the viewer’s right. On execution days crowds would gather – waiting to gawp, or mock the condemned; blood flowed into pools, we know, below the scaffold each time the blade fell. How the residents of the Hôtel de Longueville and other sites nearby felt during these near-daily spectacles we can only imagine.

Morphing Motifs

Artists, of course, had been adapting for centuries. The arabesques adorning 18th-century walls differed little, in terms of style, from the slightly more austere republican images ornamenting the ceramics below. Tricoleur cockades replaced blossoms at the ends of curling stems, or at the center of a composition.

Redefining Good Taste

The image above is part of a cup and saucer set produced at the Manufacture of Wallendorf circa 1793-1794, and for this reason this piece is important. The power of the guillotine to command and overpower is/was such that few could look away. That being the case, entrepreneurs in France and abroad moved quickly to cash in. The Wallendorf Manufactory had a long history of producing elegant ceramics for elites. Their designers simply swapped out the center subject. The gilding is of a similar quality to that adorning republican-themed ceramics produced at Sevres. The execution of Louis XVI in Paris was replicated in a variety of media. Ceramics had long been a media of political expression in France and in other nations. During the 19th century critics in France questioned the authenticity of “guillotine” plates supposedly produced in France during this time. We discuss the “birth” of this new motif elsewhere in this issue.

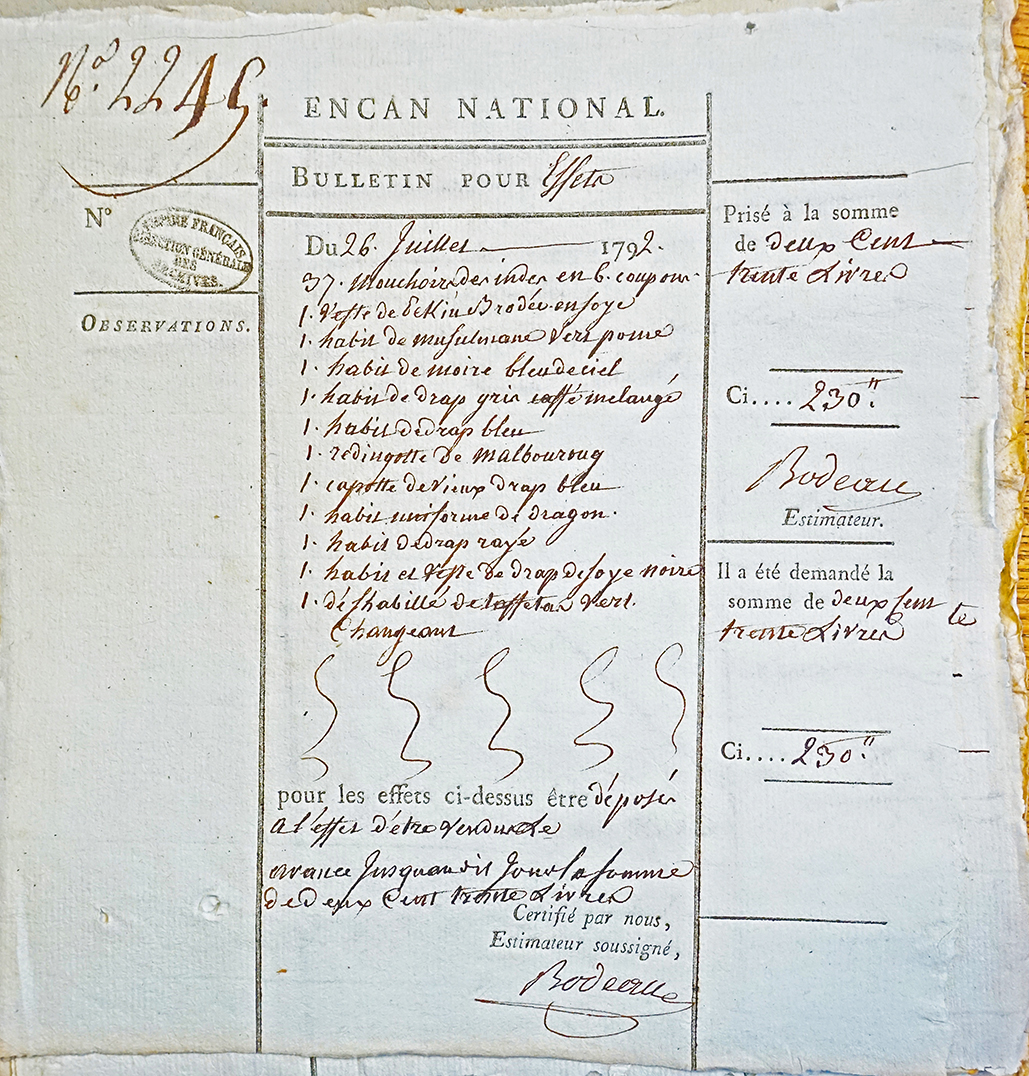

Hôtel de Longueville – Encan National

The Encan National (National Auction House) at the Hôtel de Longueville was one of the most important centers of commerce and culture in Paris. Here we see a page from the Bulletins du mois de Juillet de M. Bodeau. (The monthly record for July, 1792, of Mr. Bodeau.) Bodeau was employed as an estimateur, or appraiser, at the Encan National to value items of cloth. Bodeau judged the items listed here to be worth 230 francs. Out with the old; in with the new!

Image via the Archives Nationales (France) T//649/4 Bulletins, états d’objets, notamment de tableaux et vêtements, déposés a l’Encan national; memoire, de travaux faits à l’hôtel de Longueville, rue Saint-Thomas-du-Louvre, où était établi l’Encan…

Cartes Républicaines

Jean-Démosthène Dugourc, while working in the Hôtel de Longueville for Étienne Anisson Dupéron in 1792, designing and selling high-quality wallpaper, decided to produce republican-themed playing cards with a different associate, one Urbain Jaume. Jaume and Dugourc manufactured their playing cards (courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum) across the street (rue Saint-Nicaise) from the Hôtel de Longueville at the former Academy of Music. The cartes républicaines emerged the same change in social and political values which produced model guillotines, gilded plates from Sevres featuring revolutionary symbols, and simple homemade cockades.

Dugourc could be “daily” found at the Republican Wallpaper Manufactory in the Hôtel de Longueville at the time citizen Armand and his assistants were knocking apart the symbols of feudality fouling the storied edifice. Did the constant hammering and chiseling of stonework at the Hôtel de Longueville in the summer and fall of 1792 inspire Dugourc to try to create a new product, and profit from all this transformational destruction in some way? The production of revolutionary products had long been a regular practice by that point, as noted, so this clearly seems to be another example of the same – opportunity, ability and capital once more combining to produce new cultural objects – in this case politically-correct playing cards for every household at a price all but the poor could afford. (See our article on Jaume and Dugourc elsewhere in this issue).

Conclusion

My view is that payment, not media or aesthetics, was the most important aspect of cultural production for the vast majority of artists, artisans, authors, designers, musicians, craftspeople, entertainers and others using their talents to put food on the table, and keep the wolf from the door, in some cases almost literally.

The distinction commonly made by modern critics between the decorative and fine arts seems to me flawed. Many artists worked in a variety of media over the centuries. Very few painters inherited an income or great wealth. Théodore Géricault was very much an exception to this general rule. People with talents used their talents to earn money. Fame was nice. But fame was much nicer when it led to an increase in income and the opportunity to acquire greater wealth. My view is that a fat payday was the primarny desired outcome for any artist/craftsperson brave enough to invest any substantial of money, time and effort in a large project. Content and media were second-order concerns for the vast majority.

The marketing and promotion of the Dugourc and Jaume playing cards, for example, was thus similar to any other activity where commerce and culture were involved. Indeed, by the spring of 1793, Dugourc’s name was so closely associated with his playing cards that Anisson Dupéron was forced to pay for advertisements denying any connection between his own Republican Wallpaper Manufactory and Dugourc and Jaume’s playing card manufactory on the other side of the rue Saint Nicaise.

By February 1793, Dugourc had successfully rebranded himself. The changing values, priorities, and motifs of any given time challenged artists to adapt, and create new motifs, styles, and content which were inspired and profitable, if possible, – or else fail. The artists closest to Géricault – figures such as the Vernets and Jacques-Louis David adapted to circumstance – changed during this period, and inspired change. When the Bourbons returned to France in 1814, Dugourc once again found employment promoting and re-deifying France’s royal family.

Théodore Géricault’s own career as an artist underwent a similar process of change, experimentation, and inspiration – visible in much of his art and very much part of the commerce in culture.