André Edmond de Barras la Villette

Géricault Life

Raft of the Medusa (detail) Théodore Géricault (Salon 1819) Louvre.

Naval Heroes and Géricault Relations

André-Edmond de Barras la Villette was born in Marseilles in 1741. André-Edmond was the elder brother of Marie-Anne-Charles de Barras, an individual who played an important role in the life of Théodore Géricault and his family. André-Edmond moved with his parents from Marseilles to the island colony of Martinque in the French Antilles some time after his birth, where Marie-Anne-Charles de Barras was born. Sometime after 1756, the family unit moved from Martinique to the larger island colony of Saint Domingue. Britain and France were at war during this time. We do not know whether the British conquest of Martinique in 1762 played a part in the de Barras family’s decision to move to Saint Domingue.

Members of the de Barras family served as officers of the French navy throughout the eighteenth century. The family patron then was Jacques Melchior Saint Laurent Comte de Barras, already a senior captain and ship commander by this time.

André-Edmond de Barras la Villette followed the family tradition and began his own naval career in 1757 as a garde de la marine, the most junior officer’s rank. His training involved completing a series of six-month assignments on different vessels, during which André-Edmond served under the direct command of his uncle Jacques Melchior Saint Laurent three times. André-Edmond was recognized for his role in two naval engagements whilst serving aboard the Souverain, commanded by the Comte de Pannat. One most probably was the battle of Lagos of 1759, a two-day combat against a British fleet. This battle, deemed a British victory, was immortalized in a painting the Battle of Lagos, by Richard Paton, and in an engraving produced in 1761 by William Woollett and Pierre-Charles Canot, a French artist working in England.

The war between Britain and France ended in 1763. Five years later André-Edmond was promoted to the rank of ensign first class while serving aboard the Sultane under the chevalier de Sade in 1768.

We possess few significant details of André-Edmond’s life during the years which followed. In late 1772, while serving as an ensign on board the Folle, André-Edmond applied for leave in order to return to Saint Domingue for the “most important reasons.” By then André-Edmond had married Marie Guibert in Saint Domingue and with her produced a daughter and son. We do not know the nature of the crisis or its outcome.

In 1773, Pierre Laurent, an engraver belonging to the Academy of Marseilles, announced in the Mercure de France the sale of two new prints, one of which, Le passage du bac, was dedicated to “M. de Barras de la Villette, (sic) Enseigne des vaisseaux du Roi.” Pierre Laurent was married to his first wife Marie-Thérèse de Barras at that time. Marie-Thérèse de Barras was a cousin of the de Barras family in Saint Domingue. Laurent’s dedication was no doubt intended as a sign of affection and respect for the de Barras family service to the nation. Pierre Laurent, too, was to play a major role in the life of Théodore Géricault in Paris some three decades later, as I have discussed elsewhere.

Once France joined the United States in their war against Britain in 1778, the course of the life of André-Edmond de Barras la Villette and his family changed. By this time, André-Edmond had been promoted to lieutenant de vaisseau and served as second in command of the French frigate Résolue under the chevalier Pontevez-Gien.

In the spring of 1779, the Résolue was part of a French squadron patrolling the African coast. On the first of April, 1779, the Résolue attacked and captured the British fort of Besne on the coast of Sierra Leone, not far from Senegal. After capturing the fort, lieutenant de vaisseau chevalier André-Edmond de Barras la Villette led a party of sailors to clear away any remaining mines. One accidently exploded, killing André-Edmond. In July, 1779, the Journal Historique et Litteraire published an account of the attack and the death of Lt. de Barras la Villette on the coast of Africa in the service of France.

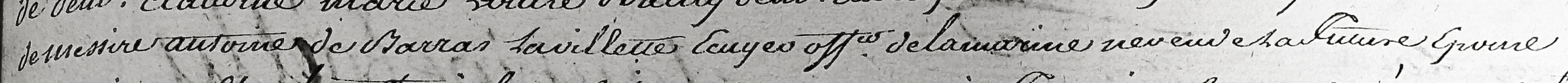

The deceased chevalier left behind his widow Marie Guibert, a daughter Madelaine-Marie de Barras, and a son Antoine de Barras la Villette – all still living in Saint Domingue.* Antoine de Barras la Villette and many other members of the extended de Barras family in Saint Domingue were present to witness the marriage contract uniting Marie-Anne-Charles de Barras and Louis-Joseph Robillard de Péronville in Le Cap on September 5, 1788.

1788 Nov. 5 Marriage contract between Robillard-Peronville and Marie de Barras (detail). Image courtesy of the Archives Nationales (France) DPPC NOT *SDOM 414

Commentary & Conclusion

Until today we had no evidence of any personal connection linking Théodore Géricault to the French navy in general, or his 1819 painting of the disastrous naval disaster of the shipwreck of the French frigate the Méduse off the coast of west Africa in 1816, in particular. Such evidence exists, it turns out.

The connections linking Théodore Géricault and the Robillard-de Barras family in Saint-Domingue and Paris are a matter of historical record, even if these connections are not broadly known. I did not discover until late in 2021, however, that Marie-Anne-Charles de Barras was actually sister to André-Edmond de Barras la Villette, and was herself a member of this important French naval family. That André-Edmond, this distant Géricault relation, actually served in the French navy off the coast of west Africa in the same waters the Méduse hoped to reach before the frigate shipwrecked on the Arguin sandback, in 1816, sounds like the stuff of fiction. That this relation died a heroic death fighting to establish French colonial interests on the coast of Africa in April of 1779, interests the colonists, soldiers, and administrators of the Méduse expedition hoped to exploit when they set sail for the same part of Africa decades later, tests the limits of all belief.

Théodore Géricault’s maternal family in Rouen undoubtably knew of the de Barras la Villette naval tradition. Géricault’s maternal grandmother, by then a widow living on the rue d’Avalasse with Théodore’s future mother, was aunt to Louis Robillard de Péronville by marriage. Her sister’s husband in Dieppe, Pierre-Antoine Robillard, was uncle to Louis Robilllard de Péronville. Are we to believe that the widow Caruel and her then un-married daughter, Théodore’s mother-to-be, were unaware of this 1788 marriage in Saint Domingue connecting their family with the de Barras family of French naval fame? Family successes were built on alliances such as this.

The links binding Théodore Géricault’s family with the Robillards in France intensified three years later with the creation of the Robillard-Caruel tobacco concern at the Hôtel de Longueville in Paris in 1791, and then again in the summer of 1797, when Marie-Anne-Charles de Barras, Louis Robillard de Péronville and their daugher Zoé arrived in Paris from Saint Domingue – shortly after Théodore Géricault and his family relocated to Paris from Rouen late in 1796, or early 1797.

The engraver Pierre Laurent, the same de Barras relation from Marseilles, was by then based in Paris. In 1791, Laurent obtained the right to produce high-quality engravings of the paintings, sculptures, and bas-reliefs housed in the royal collection belonging to Louis XVI. Laurent retained these rights after the royal collection became property of the state following the fall of the French monarchy in the late summer of 1791. Laurent, however, was unable to secure reliable government funding for this project despite the government’s support for the endeavor. Laurent pursued a variety of business models without success. Early in 1802, Louis Robillard de Péronville, Laurent’s de Barras relation by marriage, eventually agreed to finance the project.

I contend that the Robillard de Péronville & Laurent family enterprise, known first as the Musée français and then as the Musée Napoléon, played an absolutely critical role in Théodore Géricault’s decistion to become an artist, and in his artistic development during the years 1803-1809, and after. Pierre Laurent belonged to the Barras family by marriage. Widowed and remarried since, Pierre Laurent retained strong connections with the de Barras family and, as we have seen, was certainly intimately familier with the life and death of André-Edmond de Barras la Villette, a topic which we shall discuss in our next issue. Indeed, the links connecting Pierre Laurent to Robillard de Péronville via Marie-Annne-Charles de Barras make the Musée français, at least in part, a de Barras family affair.

We can safely assume that all the de Barras family members in Paris celebrated André Edmond’s service in the French navy off the coast of Senegal and his heroic sacrifice defending France’s colonial interests, formally in family gatherings, and informally on other occassions simply as expressions of love, affection, pride, honor, and loss.

The family connections linking Théodore Géricault personally to this tradition of honor and sacrifice, serving in France’s navy over generations in support of French colonial interests in Africa, and elsewhere, are significant and consequential. These facts and others compel us to re-evaluate our understanding of Théodore Géricault, his masterpiece: the Raft of the Medusa, and many of his other works. In our February issue we shall discuss in greater detail Théodore Géricault’s personal connection with André-Edmond de Barras la Villette and other members of the Barras family who lived in Paris alongside Géricault and his family.

Sources

* Fonds Marine: MAR/C/7/17, dossier 5 – Barras-La Vilette (sic) (André Edmond), tué au Sénégal en 1779, lieutenant de vaisseau. A.N. France.

* 1779 – Aug. 23 – Testament de Mad. de Barras La Villette, DPPC NOT *SDOM 406, A.N. France

* 1788 – Nov. 5 – Contrat de Mariage de M. Robillard de Perronville (sic) et Mlle. Barras, DPPC NOT *SDOM 414, A.N. France.