1862 Louise Becq to Théodore Géricault

Géricault Life

Envelope postmarked 28 March, 1862, Paris from Louise Becq de Fouquières to Théodore Géricault at the Lion d’Or (Golden Lion) in Bayeux, Calvados. Document 13 bis, Dossier Géricault, Fonds Benet, MS FR 69, Bibliothèque Municipale d’Evreux. Image courtesy of the Bibliothèque Municipale d’Evreux.

Théodore Géricault died in Paris on January 26, 1824. Readers may therefore be surprised to discover that in the spring of 1862 Louise Becq de Fouquières, the niece of Pierre de Dreux D’Orcy, sent a letter to Théodore Géricault alive and well at the Lion d’Or in Bayeux, which included family news and a plan to “produce a sort of Biography” of his father.

In fact, Louise Becq de Fouqières was writing to Georges-Hippolyte Géricault, Théodore Géricault’s only known child. Georges-Hippolyte was born in Paris on August 21st, 1818. As a young man, Georges-Hippolyte sought the legal right to use his father’s name. This petition was granted on December 10th, 1840. Some time before 1842, Georges-Hippolyte began using his father’s given name as well as the Géricault family name.

The letters Louise Becq de Fouquières sent to Georges-Hipppolyte “Théodore” Géricault, and those sent by Pierre de Dreux D’Orcy, Eugène Lami, and other individuals were discovered by accident in 1972 by the archivist Michel le Pesant. Le Pesant’s find transformed Géricault scholarship. It was from another letter by Louise Becq de Fouquières that we learned that Alexandrine-Modeste Caruel de Saint-Martin, the young wife of Jean-Baptiste Caruel de Saint-Martin, Théodore Géricault’s maternal uncle, was actually the mother of Georges-Hippolyte. The letters Georges-Hippolyte received from Louise Becq de Fouquières, and others, thus open an invaluable window into the life of Théodore Géricault, Georges-Hippolyte – his only child, Alexandre-Modeste Caruel de Saint-Martin, the lives of the de Dreux and Becq de Fouquières families, and other key figures in Géricault’s circle.

Georges-Hippolyte’s decision to take his father’s given name was natural enough, in a sense. The child had been named after his paternal grandather Georges-Nicolas Géricault at birth, and taken to live with a couple in Normandy. We have no evidence that Georges-Hippolyte had any direct contact with either of his parents during his life. Georges-Hippolyte may have adopted his father’s given and family names in an effort to create a posterity he was denied, and to forge a bond of sorts with a father he knew of only by reading books, looking at paintings and drawings, and listening to stories from his father’s friends.

In our October issue of 2020, we continue to examine the role that Pierre de Dreux D’Orcy, one of Théodore Géricault’s closest friends, played in shaping Géricault’s public persona during the years following the painter’s death. Louise Becq de Fouquières, in her letter to Georges-Hippolyte of March 28, 1862, informs Georges-Hippolyte of family plans to aid D’Orcy in his efforts by producing “une sorte de Biographie de ton père.” Louise also provides an illuminating description of Pierre de Dreux D’Orcy’s state of mind and health around the time her uncle was in contact with Ernest Chesneau, just as the critic was about to publish his essay on Géricault in book form in the spring of 1862. (See our article on Chesneau and d’Orcy elsewhere in this issue.)

“…A Sort of Biography of Your Father…”

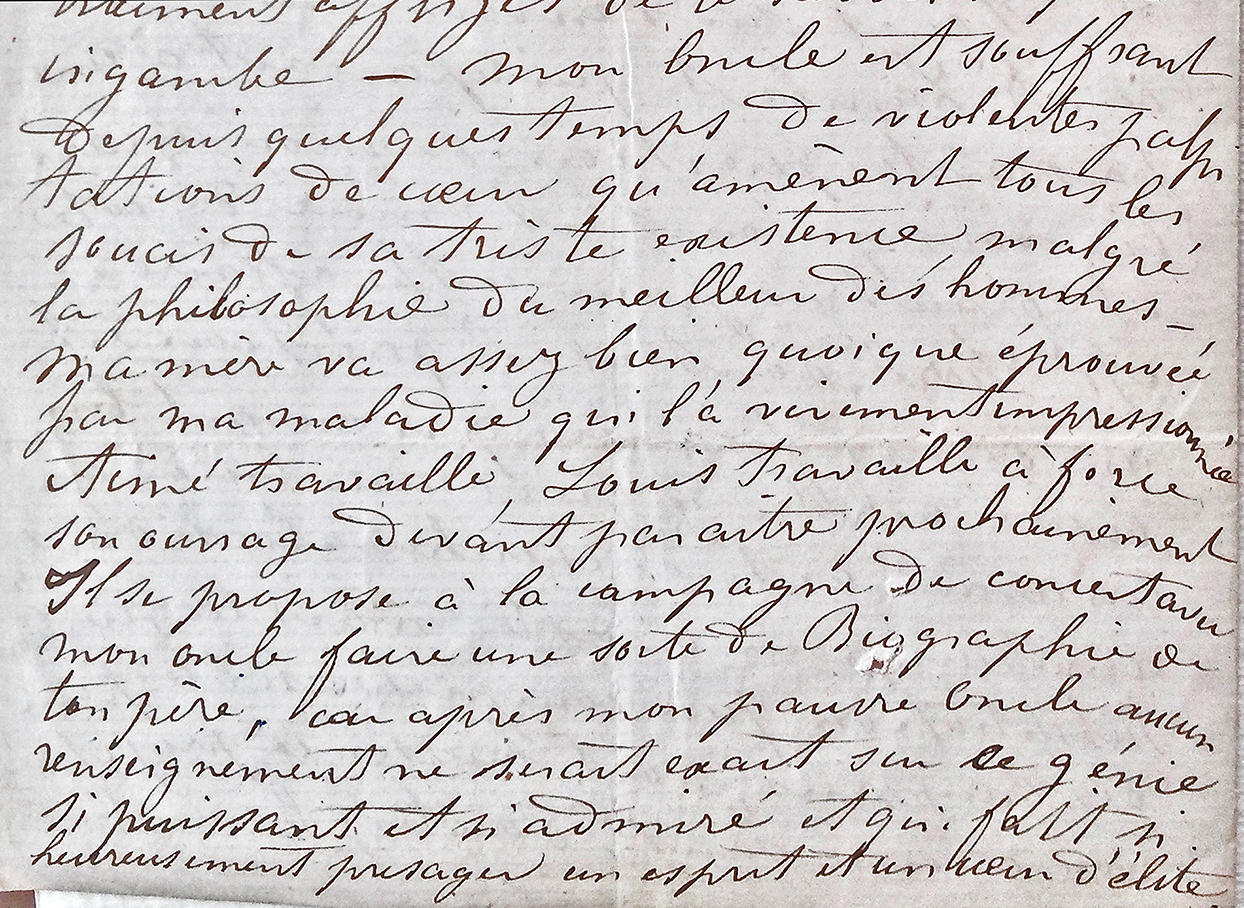

Letter (detail) from Louise Becq de Fouquières to Théodore Géricault at the Lion d’Or (Golden Lion) in Bayeux, Calvados. Document 13, Dossier Géricault, Fonds Benet, MS FR 69, Bibliothèque Municipale d’Evreux. Image courtesy of the Bibliothèque Municipale d’Evreux.

Louise Becq concludes this letter on a separate page, informing Georges-Hippolyte that her own ill health prevents her from travelling. The penultimate passage below provides ample material for further investigation and discussion. In Louise Becq’s letter “Aimé is her husband: Aimé-Napoléon Becq de Fouquières; and “Louis” is Louis-Aimé-Victor Becq de Fouqières, their son. “Mon Oncle” (My Uncle) is Pierre de Dreux d’Orcy; “ton père” (your father) is, of course, Théodore Géricault.

” – Mon Oncle est souffrant – My Uncle has been suffering from violent palpitations of the heart for some time, brought about by the worries of his sad existence, despite the philosophy of the best of men. My mother is well enough… Aimé labours, Louis is working hard to finish his current work. He proposes a joint effort with my uncle to produce a Biography of your father, for after my poor uncle there will be no accurate information on this genius, so powerful and so admired, which so happily presaged a spirit and a heart of the highest order.”

Conclusion

Louise Becq’s letter confirms that in March of 1862 Pierre de Dreux D’Orcy was experiencing enough stress to cause violent heart palpitations, and had been for some time. Attributing D’Orcy’s stress-related heart problems entirely, or mostly, to the challenges of managing Théodore Géricault’s public reputation, and his negotiations with Ernest Chesneau in 1862, in particular, would be unwise. That said, Chesneau’s refusal to accede to D’Orcy’s attempts to interfere with the content of Chesneau’s upcoming book can’t have improved D’Orcy’s state of mind, or his health. In 1836, Victor Darroux, explicitly refuted charges that Théodore Géricault sought an early death through his unrestrained pursuit of violent pleasures, the prevailing view at that time established by Alphonse Rabbe, the historian, during the late 1820s. Darroux publicly credited D’Orcy as the source for his Géricault piece. (See the September, 2020, issue.)

Assisted by D’Orcy in 1841, critic Louis Batissier went further:

“To be clear, we make no attempt at rehabilitation; for no soul speaks of Géricault today with anything but just admiration for the work of this artist…” (Revue du Dix-Neuvième Siècle, 1841 – See our January, 2019 issue.)

Times changed, however. In 1848, Jules Michelet presented a portrait of Géricault: “with the eye of a predatory bird” lost in the pursuit of pleasure. In 1851, Gustave Planche published details of Géricault’s suicide attempts and self-destructive passions. A new narrative took root, one which questioned elements of Géricault’s artistic talents in places, as well as his character. Confronted by this new narrative, Pierre de Dreux D’Orcy in 1862 found his ability to shape Géricault narratives much diminished, at least as far as Ernest Chesneau was concerned.

Louise Becq de Fouquières’ letter tells us much more, however. Without Louise Becq’s letter, we knew only that, throughout his life, Pierre de Dreux D’Orcy did his best to shape Théodore Géricault’s public persona following the painter’s death in 1824. Other individuals contributed anecdotes and valuable information. But we had no sense whether any other specific individuals were committed, in the larger sense, to ‘protecting’ the narrative D’Orcy helped construct from 1836 on, and to guarding Géricault’s secrets.

Louise Becq’s letter informs us that in 1862 others shared D’Orcy’s concerns. Louis-Aimé-Victor Becq de Fouquières, a formidable scholar and hommes des lettres in his own right, proposed that he and D’Orcy produce a new biography of Théodore Géricault together. Did Louis-Aimé propose this collaboration as a response to D’Orcy’s unsuccessful attempts to interfere with Chesneau’s soon to be published book? Did Chesneau inform D’Orcy in late 1861 that he planned to publish his account of Géricault’s suicide attempts largely intact in May of 1862? Did this knowledge have an adverse effect on D’Orcy’s health?

We do not know. Nor do we know whether Aimé’s proposal was serious, or simply an attempt to lift his older relation’s mood, and improve his health. Or both. The letter confirms that in 1862 other family members, including some born after the painter’s death, were aware of D’Orcy’s efforts and the problems D’Orcy had encountered. Over the years, these individuals, too, had become troubled by the evolving public Géricault narrative, a narrative which by then included reports of Géricault’s suicide attempts. This letter confirms that Louis-Aimé-Victor Becq de Fouquières was willing to act on these concerns.

Who else might be among those worried about charges that Théodore Géricault tried to take his own life? Louise Becq identifies one such individual who must have been extremely concerned the painter’s true biography: Georges-Hippolyte, Théodore Géricault’s son. The letter is written to Georges-Hippolyte, for his eyes alone, not for posterity. We can detect an urgency and passion in her words when she writes to Georges-Hippolyte that his father,”ton père,” a figure Georges-Hippolyte never met, and could never meet, was not only a man of immense talent and strength, but one who possessed a heart and a spirit of the highest order.

As noted earlier, Georges-Hippolyte could only know his father through paintings and drawings, stories told by his father’s friends and family members, and through the books he read. Taking his father’s given and family names helped, as did the assurances of family members. Yet, in the books and articles produced after 1848 Georges-Hippolyte discovered the story of a different father: a weak man, a slave to his pleasure and passions, lacking the courage to face life, and morbidly seeking his own death – in effect abandoning his only son a second time, denying the child, now a man, any chance of paternal love.

Louis-Aimé-Victor Becq de Fouquières and Pierre de Dreux D’Orcy did not produce a new biography for Georges-Hippolyte to read. Ernest Chesneau published his essay on Géricault intact in 1862, and appended Michelet’s 1848 account of Théodore Géricault’s self-destruction as an appendix to the text. A second edition of Chesneau’s book was published in 1864, with the same account of Géricault’s suicide attempts, again with Michelet as an appendix.

Louise Becq de Fouquières’ letters confirm she did her best to comfort Georges-Hippolyte, not just in 1862, but over the course of his life. Others made similar efforts. We need to ask now, however, who else might be as keenly interested in Georges-Hippolyte’s happiness and well being? Who else might hope to guard the secrets Théodore Géricault’s friends and companions held fast?

Photo of Louise Becq de Fouquières Document 1, Dossier Géricault, Fonds Benet, MS FR 69, Bibliothèque Municipale d’Evreux. Image courtesy of the Bibliothèque Municipale d’Evreux.