1866 Bathild Bouniol – Géricault

Géricault Life

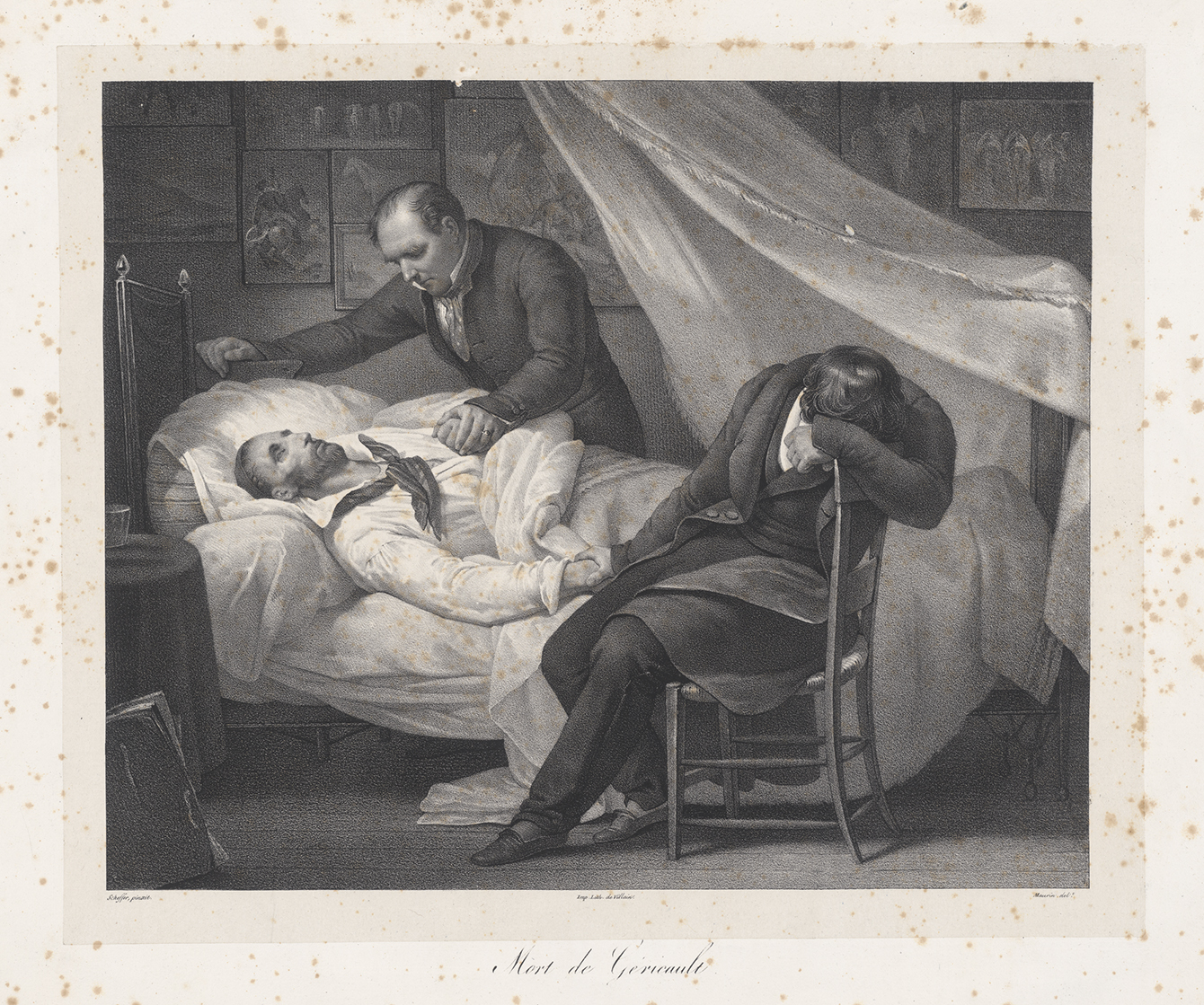

Mort de Géricault (detail) Ary Scheffer, 1824, Musée de Ary Scheffer.

Bathild Bouniol is a new name for almost all modern Géricault scholars, despite the fact that Bouniol was a contemporary of Ernest Chesneau, critic, and historian. Bouniol’s essay: “Géricault – Sa vie, Son œuvre” (Géricault – His Life, His Work) draws upon Charles Blanc, Ernest Chesneau, Alphonse Rabbe, and several others. Bouniol’s essay was published in the Revue du Monde Catholique in 1866.

Bathild Bouniol’s Géricault

While Bathild Bouniol’s essay on Théodore Géricault offers readers little that is new in terms of pictorial analysis, Bouniol addresses squarely the state of Géricault criticism in 1866. Rabbe examines the question of Géricault’s suicide attempts and the authority of Nicolas Toussaint Charlet, Géricault’s companion, by drawing on sources rarely cited in modern Géricault scholarship, sources such as Alphonse Rabbe.

“Géricault – His Life, His Work“

“…his first painting: the Scout of the Imperial Guard, much remarked upon at the Salon of 1812, brought Géricault’s name before the general public. The scout of the Imperial Guard is represented in his picturesque uniform, climbing a steep slope and turning back towards his brothers in arms, as if to call them forward to charge against the enemy. This study is full of energy; the positioning of the horse reveals an extraordinary facility to deal the with gravest compositional difficulties; it is an equestrian Michelangelo. There is, perhaps, something in the attitude of the man which recalls a rider of the circus; but in terms of color, movement, independence of style and firmness of design, the piece is absolutely a work of the highest quality.

The pendant which the artist gave to the Scout two years later, the Wounded Cuirassier, merits no less an elegy; and we are inclined to even prefer this second page, imprinted with a grave, mournful and profound poetry. Here, notes one judicious biographer, [Gustave Planche] the Cuirassier is revealed by an expression of resignation, by a simple pose, eyes raised to the sky, as if to conjure away all the evils which fell upon the French army during the retreat from Moscow, his emaciated features twisted by suffering and misery. Following behind him, his horse shares in all the misfortunes of his master. This is no longer the noble courser with the fiery eye, nostrils enflamed, rump shining and well-nourished; this is the wounded horse, broken by fatigue and hunger, and whose impressionable soul absorbs all the cares of his master to whom he is so closely bound. We see points of brilliant color, points of diaphanous ice, and other plays of light; all is cold like the Russian sky, sombre like the subject, gray and dirty like the two companions, the blasted earth one seamless sheet.

As we can surmise from the preceding passage, this critic, who was writing in 1856, saw an episode from the Russian campaign in the painting. This opinion, adopted by the public, and which was seen as some sort of prescription, was recently contested by Mr. E. Chesneau (1. Les Chefs d’école. [1862]), whose contrary view would carry more weight had he offered, in support of his opinion, something other than an assertion free of any proofs. “To discover the mournful symbol of our reverse on the icy plains of the North within the Wounded Curassier requires an act good will.“ So states Mr. Chesneau. But will this trenchant declaration suffice to overturn a reading of the painting which has since become almost a legend.

Should we now believe what Rabbe tells us of the character of Géricault?

‘The first and brilliant successes of the artist had an adverse impact upon his studies, not by exciting his pride, but in placing him in society with all its dissipations. Géricault plunged into this crowd of lively and impetuous passions with a character which was very weak. Unhappily, he possessed enough of a fortune to fully indulge his penchant for pleasure. Even worse, several of his friends, and those who pretended friendship, abused him and took advantage of his easy disposition, leading him into all the kinds of excess which comprise the development of talent and personal stability.’ [Alphonse Rabbe, Biographie Universelle, 1826*]

Nevertheless, Géricault did work at intervals; and during a moment when his reason returned he resolved to quit Paris and travel in Italy. He consecrated fifteen months to this enterprise. Upon his return, he busied himself preparing his studies for his Shipwreck of the Medusa, a painting which was in no sense the product of improvisation…

…a grand and magnificent career lay before the artist, there for the taking. He envisioned vast projects…But suddenly he came crashing against the reef which was fatal to so many others, including Raphaël himself: the passion for pleasure… If one believes a biography already cited which does not appear in any sense disposed towards malevolence: “More than ever, Gericault returned from Italy with the appetite for the most tempestuous pleasures, which had only been increased by the passionate gallantry of the inhabitants…”

Travel to London did nothing but exite the appetite of the artist for the hunts, the dogs, the horses, the violent recreations. However, amidst this crowd, in the delirium of this storm, was he happy? Very far from it! Reproaching himself for his idleness – this life of dissipation and emptiness, from which he did not have the courage to tear himself away, he tumbled into sadness. Amidst the bitter discouragement, this state of profound boredom, this terrible ennui of the lost, so wrongly called “the happy of the world,“, he succumbed upon the banks of the Thames to this fatal endemic malady, a malady so often incurable, the outcome of which is usually tragic. Yes, seized with vertigo, this great spirit, this noble heart, this man of genius, to whom glory promised the most magnificent future almost fell prey to the monster, teetering close to the abyss which would so sadly later swallow up Leopold Robert and Gros. Here is the account of the colonel La Combe and told to him by Charlet, the travelling companion of Géricault:

Charlet, upon returning to the hotel very late at night, learned that Géricault had not stepped from his room the entire day. Fearing some sinister project, he went straight to Géricault’s room, knocking once without obtaining a response, he knocked again. As there was no response, Charlet forced open the door. He was in time! The stove still burned and Géricault was unconscious upon his bed and with some assistance recalled him back to life. Charlet then cleared everyone from the room and sat down close to his friend.

‘Géricault,’ said he, in the most serious manner, ‘we see that you have tried to take your own life several times. If this is the path you will take, we can do nothing to stop you. You will do as you wish in the future, but allow me to offer this word of advice at least. I know that you are religious: you know well that once dead, it is before God that you must appear and give account. How will you respond, unhappy one, when he interrogates you? …After all, you did not merely dine.’

This sally, more than suprising after what had just preceded, and most unexcpected, caused Géricault to burst into laughter. He promised to never again make similar attempts, thus, this happy result excuses Charlet. His biographer colonel La Combe includes an observation made by Gustave Planche: “This discourse is a curious mix of affection and raillery; his unique approach will surprise no one familiar with the banter of Charlet. Raillery was, in him, a gift so evident and a talent so imperious, that it could not fail to inducesmiles during the most solemn occasions. Had Charlet employed the language of philosophy, or religion, and addressed Géricault seriously when attempting to deter him from seeking death, perhaps he would not have succeeded: raillery, by re-animating the vital force of gaiety in the soul which had sought death, came to the aid of religion and philosophy.

So says the colonel in his commentary, for which he alone is responsible. Mr. Ernest Chesneau, after having cited this passage, alerts us in a note that he had heard that Mr. Dedreux Dorcy, éericault’s most intimate friend, had protested vehemently against these allegations and declared the scene of suicide to be a fable invented by Charlet. Invented! Why? To what end? Does this not indict Mr. Charlet somewhat? And Mr. Dedreux Dorcy, who was not, I believe, in London, at the time of this event, does he not let himself be led astray by his loyalty, which is, of course, so laudable, to preserve intact a precious memory? Let us not forget too quickly the counsel of philosophy: Amicus Plato, sed magis amica veritas? (Plato is my friend, but Truth is a greater friend.)

To support this opinion, I will recount how Charlet became friends with Géricault, from an account by Charlet himself much later taken from one of his letters published by colonel La Combe. In the year, 1818, Charlet, still little known, had been contracted by Mr. Jukel (sic) to work as a painter, decorator, and philosopher and tasked with decorating the inn known as the Trois Couronnes (Three Crowns) in Meudon. Charlet recalls:

‘I was fully engaged with my work when I was requested to ascend to the first floor, where the inn-keeper awaited me; there I found a happy group at table, dining and conversing; one individual stepped forward and introduced himself as Géricault, adding:

– You do not know me, Mr. Charlet; but I, I know you well and hold you in high esteem. I have seen your lithographs, which could only come from the pen of a hero. If you would like to join us at our table, you would please and honor us.

How delightful, gentlemen! I responded, but all the pleasure and honor is mine.

So, I took a place at the table, and all passed well, so well that from this day forth a friendship was forged which only death could sunder. Poor Géricault! How excellent was the heart of this honest man and great artist!’

If Charlet described their friendship in these terms, is it probable – is it even possible – that the man who spoke so would construct a story of suicide for the sole pleasure of muddying the memory of his friend, and which would bring neither honor, nor profit to himself?

That which I stated above regarding Mr. Dedreux Dorcy, I will repeat again as a reply to these other panegyrists, those who do not admit there was at least a shadow of truth in these accounts, which they dismiss as nonsense peddled by the mean-spirited and which they claim were too easily accepted by the journals of the time. Moreover, these less-flattering versions of events were also adopted by the greater number of biographers which were in no sense hostile towards Géricault (la Biographie Universelle, la Biographie de Didot, etc.).

Mr. Darroux, however, citing Mr. Dreux Dorcy as his source, indignantly rejects these assertions in the Dictionnaire de la Conversation et de la Lecture: “Some have suggested that Gericault was principally responsible for his own death, he whose existence was nothing but an intellectual struggle against the coolness and the indifference of his century! Envy, which pursued him through his life, could not stop even before his tomb.”

All of us, so bound by feeling to the illustrious painter, we would be happy to place our faith in these assertions. But before other claims no less precise, emanating from serious men who are, we have noted, in no way hostile to Géricault, it seems difficult not to doubt a little, and not incline towards this conviction, that the friends of the great artist, by an excess of zeal, make history too cheap, or better, are the first to be duped by a generous delusion. Mr. Ch. Blanc however, who is not suspect, and who, moreover, again and again relies on the testimony of Dedreux Dorcy, offers his views in a way which seems to us to cut short the uncertainties:

‘Géricault, said he, was then a handsome young man, taller than average, elegant and well formed, who was loved by women and loved in return, was already well-known at the races of the Field of Mars. In our day he would have been a member of the Jockey Club, one of the heros of Chantilly, and of the steeple-chase, a young lion in the fullest brilliance of the word, but the pleasures, the mad cavalcades did not harm Géricault’s studies … in a word, they provided material for his favorite observations, and it was the painter himself who went into the woods!’

Suffice to say that this last assertion, contradicted by the facts, is not our own. Whatever may be said, the one issue which is beyond doubt is that the unfortunate young man, already gravely ill, returned to Paris fully resolved, it appears, to recommit himself to his work. A resolution too late and which catastrophe would not allow him to realise! A fall from a horse created a lesion in his spine, and from this a tumor, from which Géricault succumbed on January 18, 1824. We have one remarkable detail of this event! Like Prud’hon, in his studio he left a great religious painting, nearly finished, which he began when his hand was already almost too weak from pain to hold a brush. This Descent from the Cross, we can be assured, was executed with all the elevation of style and the severity of tone which distinguishes the best productions of the Lombardy School. It is a new proof of the religious sentiment which had conserved Géricault amidst his regretable diversions, a sentiment which, one can hope, would have offered consolation during his long and cruel agony…

His faithful companions surrounded him during his long descent and remained around his sad bedside until the final moment. All friends of the arts must pronounce with respect the names of Mr. and Mrs. Bro, Dedreux Dorcy, Ary Scheffer, who consecrated a painting to the memory of the painter, of small size, but of a profound sentiment, reproduced and widely known as a lithograph. We advise these young souls too inclined to lend an ear to pernicious influences and the seductions of pleasure to place a copy of this image in their own studios in clear view, and meditate upon it from time to time, above all when they are solicited by temptation, like Ulysses by the song of the Siren. For this image is the faithful reproduction of the unfortunate artist, who Rabbe tells us is represented in the last instants of his agony which the sufferings and abuse of life had upon him, a form very changed from what he had been before the treasures of such a rich youth and such a handsome talent had been devoured…”

* Biographie universelle et portative des contemporains, ou Dictionnaire historique des hommes célèbres de toutes les nations, morts ou vivants, qui, depuis la révolution française, ont acquis de la célébrité par leurs écrits, leurs actions, etc: Par une société des publicistes, de législateurs, etc. Ouvrage entièrement neuf, Volume 2, Paris, Au Bureau de la biographie, Alphonse Rabbe main author, Sainte-Preuve , joint ed., Boisjolin, Claude Augustin Vieilh de 1788-1812, joint ed. 1826 [more likely 1828 and then in volume format 1834] (pp.1861-1863)

Bouniol – D’Orcy – Suicide

Bathild Bouniol publicly identifies Pierre de Dreux D’Orcy as Géricault’s friend and then argues this friendship makes d’Orcy a suspect source, especially on the question of Géricault’s suicide attempts. Indeed, Bouniol attacks D’Orcy, while defending Nicolas Toussaint Charlet. Bouniol also draws attention to D’Orcy’s efforts to shape Ernest Chesneau’s 1862 essay on Géricault, an essay Chesneau published originally in 1861. Moreover, Bouniol repeats some other charges regarding Géricault’s character and mental health problems raised by other sources, Alphonse Rabbe among them. Modern scholars have yet to identify Rabbe as the author of the first biography of Géricault in the Biographie Universelle et Portative, but Bouniol clearly attributes this profile to Rabbe. We present Rabbe’s 1826 profile of Géricault elsewhere in this issue.

Mort de Géricault (Death of Gericault) Charles Morrin, Imprimerie Villain, 1825 (Courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery)