1812 Pierre Robillard – Duel

Géricault Life

L’Epave (detail) Théodore Géricault – Musée des Beaux Arts Rouen

Théodore Géricault – 1812

1812 is generally recognized as a watershed year in the life of Théodore Géricault. That spring Théodore lost his maternal grandmother Louise-Thérèse De Poix (Caruel), who died in Paris on April 10th, 1812. Two months later, in June, Théodore inherited one quarter of his grandmother’s estate. In the late fall of 1812, Théodore presented his Portrait équestre of M. D⁜⁜⁜ (the Charging Chasseur) at the Paris Salon, winning official recognition as an artist for the first time at the age of 21 and a gold medal for his efforts, as well as a mixture of praise and abuse. This account of loss, fortune, success and disappointment in the life of Théodore Géricault in 1812 is a critical part of the firmament of all modern Géricault studies.

In fact, the first Géricault family catastrophe of 1812 occured two days before the death of Théodore’s grandmother on April 10, that year. Sometime after 1:00 pm, on April 8, a cab driver discovered the body of the Chevalier Pierre Robillard, Théodore’s youthful cousin, deep in the woods of the Bois de Boulogne just west of Paris, dead before his 27th birthday. Pierre and his parents Jacques-Florent Robillard and Angelique-Louise Morize were key members of Géricault’s maternal family. Indeed, the death of Pierre Robillard on April 8, 1812, may well have contributed to the death of Théodore’s grandmother, Louise-Thérèse De Poix, two days later on April 10. Louise-Thérèse had known Pierre Robillard from the time of his birth in 1786. Pierre Robillard was her (only) sister’s nephew by marriage. In fact, the tragic circumstances preceding the death of Théodore’s grandmother eerily resemble the tragic circumstances precending the death of Théodore’s mother in the spring of 1808, a similarity which will have been lost on nobody within the family circle.

Pierre Robillard’s premature demise certainly crushed the life from his ailing mother, Angelique-Louise Morize, who had already suffered a similar crushing blow when she and her husband lost their second child, Amédée-Selim Robilllard, age 15, in Febrary, 1808. Angelique hung on for five weeks after the death of her sole surviving son before expiring in her Paris apartments on May 18, 1812. The fact that Angelique-Louise and her husband Jacques-Florent Robillard (the recently enobled Baroness and Baron de Magnanville) had recently celebrated the marriage of their only surviving son, Pierre, to Bonne-Emilie de Nanteuil on December 12, 1811, in Paris, made Pierre’s tragic and unlooked for end all the more devastating for all concerned.

Indeed, the deaths of Pierre Robillard and Louise-Thérèse De Poix in April, 1812, set in motion a series of events which transformed the family dynamics of Théodore Géricault’s immediate and extended family. We will discuss these transformations in greater detail elsewhere in related articles. Our interest here is to examine the impact of the death of Pierre Robillard upon Théodore Géricault. Our first task is to identify key archival documents which allow us to better gauge the disaster’s impact upon Théodore Géricault and upon his family. We begin with the official report of Pierre Robillard’s death which appeared in the Bulletin de Police of April 10, 1812, below.

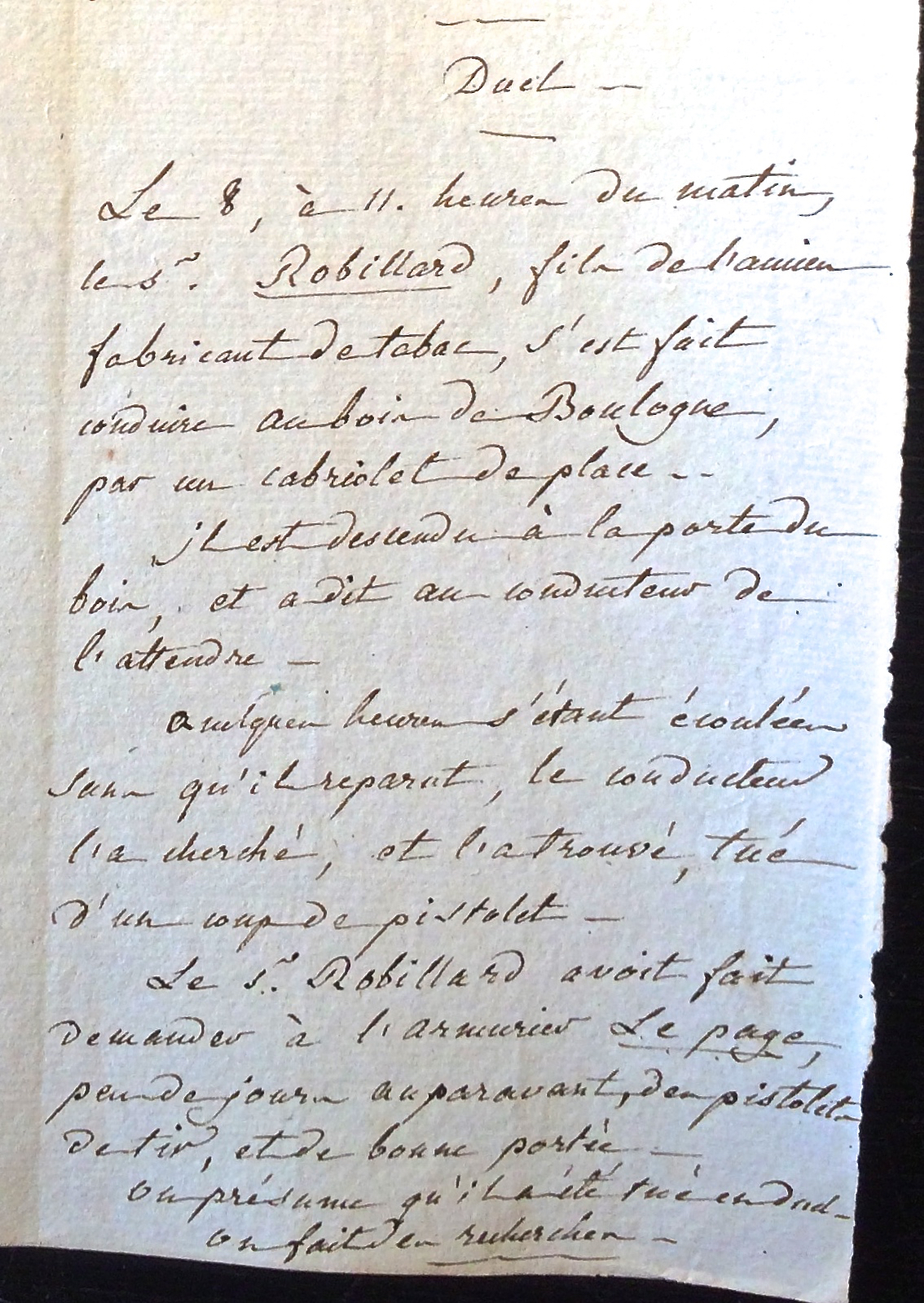

Police Report: Death of Sr. Robillard

Bulletin de Police du 10 avril 1812, Rapport de 9 avril: Duel, (detail) F/7/3776 Archives Nationales (France)

“…The 8th, at 11 o’ clock in the morning, Mr. Robillard, son of the former tobacco manufacturer, was conducted to the Bois de Boulonge (woods west of Paris), in a two-person cab. He exited the cab at the entrance of the wood and instructed the driver to wait. Several hours having passed without his return, the driver searched for him, and discovered him killed by a pistol shot. A few days before Mr. Robillard had requested from Le Page a pair of duelling pistols, with a good range.* One presumes that he was killed in a duel. The investigation is ongoing…” (* Jean Le Page, of Fauré Le Page, was the premier designer, manufacturer, and purveyor of blades and fire arms at this time.)

Commentary

We begin by stating the obvious: grief is personal – each of us processes loss in our own way, but some commonalities hold true, the first being: the fact of Pierre Robillard’s death mattered far more to Théodore Géricault, and other family members, than the manner of their loss. Again, to state the obvious: the death of a daughter or son is equal to, or greater than, the loss of a grandparent or parent. And the loss of a nephew or niece, grand-daughter, or grandson, can be almost as devastating as the loss of a son, or daughter because of the devastation wrought on all the family members who ‘survive’ the loss. We experience the grief of those we love as much, or more than, we do our own. The sense of loss for those close to Pierre Robillard was profound.

We know little of Théodore’s relationship with his Robillard cousin Pierre at this time. In the spring of 1812, Théodore Géricault lived about 300 meters from Pierre Robillard and Bonne-Emilie de Nanteuil, and the Baron and Baroness Robillard de Magnanville who all lived together, it seems, in the family home at 22 rue de Mont Blanc. Théodore Géricault lived with his father at 8 rue de la Michodière in a home owned by Charles Biancour, a former partner in the Robillard tobacco concern. Théodore first came in contact with his Paris Robillard relations no later than 1796 or 1797, when the Géricault-Caruel family relocated to Paris from Rouen.

Théodore was likely somewhat awestruck by his older cousin Pierre, even at as a child. Pierre was born in Paris on July 4, 1786, and five years older than the new family member from Rouen. Pierre Robillard, moreover, belonged to a far richer family and was, in 1812, the sole son of a Baron of the Empire, a title Pierre would inherit along with his family’s money and lands. Théodore was closer in age to Pierre’s younger brother Amédée-Selim Robillard, until Amédée’s death in 1808, and to his Saint Domingue cousins in Paris: Zoé Robillard de Peronville and Charles-Joseph Robillard.

Amédée-Selim Robillard, Pierre’s younger brother, was born on October 4, 1792, and was almost exactly a year younger than Théodore, who was born on September 26, 1791. We have speculated that Amédée-Selim and Théodore celebrated birthdays together at family gatherings. However close the boys may have been, that bond was broken when Amédée-Selim died on February 2, 1808. Worth noting is that Amédée-Selim’s death preceded that of Théodore’s mother, Marie-Jeanne-Louise Caruel (Géricault) by some five weeks. Marie-Jeanne-Louise Caruel passed on March 15, 1808, leaving behind her husband, Georges-Nicolas Géricault, his mother, and Théodore – an only child of 16 who never forgot his mother’s death.

Conclusion

Théodore Géricault’s keen interest in death was remarked upon during his lifetime, by his 19th-century biographers, and by critics today. We may better understand why, in part, now that we have a clearer understanding of the unusual role death played in the early life of the artist. Any single explanation for any such an interest must be rejected. By the same measure the events of Géricault’s youth cannot be ignored, especially events as traumatising as these. Contemporary witnesses attest to the depth of Géricault’s lasting grief over the loss of his mother. We have no reason to doubt this claim. Modern scholars have long known how Théodore responded to the death of his grandmother in April of 1812. Théodore’s right to study painting at the Louvre was rescinded following two separate violent exchanges – the first with staff on some unknown date, and the second in May, 1812, when Géricault struck another student. Théodore was allowed to return to the Louvre only after the intervention of his teacher, Pierre-Narcisse Guérin.

We can see clearly now, however, that in the spring and early summer of 1812, Théodore Géricault was not just suffering the loss of a single beloved relation, a relation whose much mourned passing must have been in some sense anticipated. Géricault’s grief was far deeper and more complex. His grandmother’s death was bound up in and preceded by the shock of the death of his young cousin Pierre Robillard 48 hours before. At the same time, Théodore was also re-experiencing the loss of his mother and his younger cousin Amédée-Selim Robillard, who died weeks apart just four years before in 1808. That death of Amédée-Selim, a year younger, made death real for Théodore in ways that the passing later of Théodore’s much beloved mother never could, irrespective of the much greater sense of loss and grief his mother’s passing induced in the artist. Death came for all, young and old. Different deaths imposed upon a boy of 16 early in 1808, different degrees of loss – both significant for different reasons, both deaths inextricably bound together as permanent features of Théodore Géricault’s conscious and unconscious memory.

Géricault’s trauma of 1808 was replicated and re-experienced with the same lessons in the spring of 1812 compounding his sense of loss. And Géricault was not alone. We have already discussed the impact of Pierre Robillard’s death upon his mother Angelique-Louise Morize, re-experiencing the death of her second son Amédée-Selim in 1808, memories awakened by the unthinkable, but all too real death four years later of her first and only surviving son Pierre, precisely when life seemed finally so full of promise. Many other family members were experiencing a similar horrific and seemingly interminable sense of deja-vu, re-awakened by the recent loss of a parent, a son, a cousin, a nephew, or a spouse.

In the spring and summer of 1812, a shroud of collective and individual grief hung over Géricault’s immediate and extended family. Théodore’s life must have been a waking nightmare – one long, lonely state of profound grief interrupted by the absurd banalities and emptiness of life’s everyday duties and demands – memories of his much missed mother and grandmother, his cousins – flooding uncalled for into his mind, insistant and always irresistable, – his own sadness mirrored in the faces of his uncle Jean-Baptiste Caruel and Alexandrine-Modeste de Saint Martin, his uncle’s young wife, who joined the family in 1807.

Alexandrine-Modeste de Saint Martin, present to mourn the passing of her husband’s sister – months after her own marriage in 1807, – Alexandrine present to ease the passing of her husband’s mother in 1812, Alexandrine a mother herself by then, – Alexandrine, present to help her husband’s favorite nephew Théodore, a boy of 16, survive the loss of his mother, – Alexandrine, present to help Théodore, a young man of 20, survive the traumas of 1812. Little wonder that trouble erupted at the Louvre that May. Little wonder that Angelique-Louise Morize did not survive the deaths of both her sons. Little wonder Théodore Géricault and other family members were unable to move completly past the deaths of Louise-Thérèse de Poix and Pierre Robillard days apart in early April, 1812. Little wonder that these deaths had real and unimaginable consequences.